Minnesota cities seeking more time to cut salt from wastewater

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

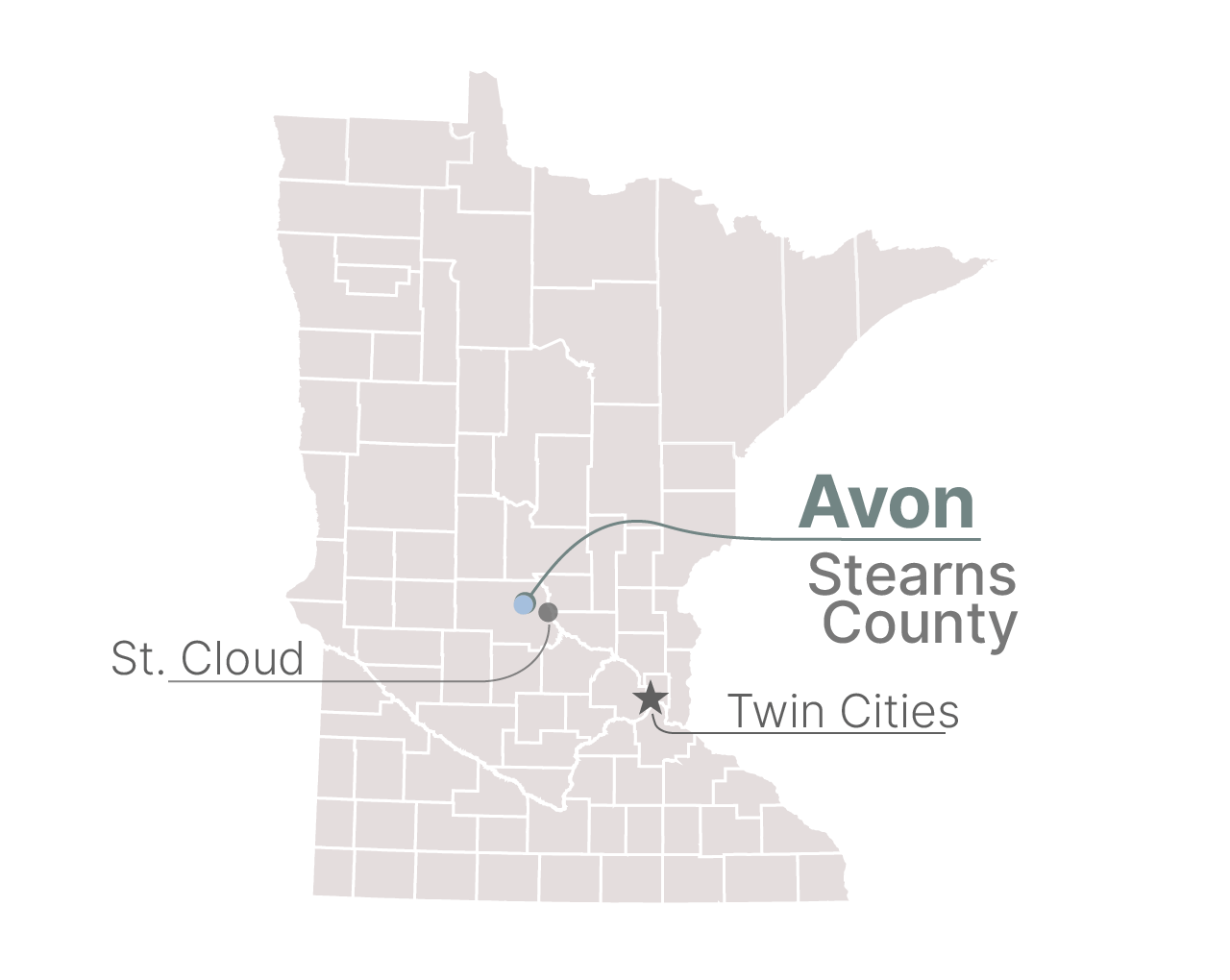

Like a growing number of Minnesota cities, Avon is grappling with a salty problem.

State regulators say Avon's wastewater treatment plant is releasing too much chloride — salt — into nearby Spunk Creek, which empties into the Mississippi River. The likely source: Home water softeners.

Reducing the city's dependence on salt will be challenging and costly, so Avon is asking for more time — 15 years — to come up with a solution. It's the first Minnesota city being considered for a variance to chloride limits under the federal Clean Water Act.

Avon is one of about 100 Minnesota cities discharging too much chloride from their wastewater plants. Chloride is a permanent pollutant, and excess amounts can affect fish and aquatic life in rivers and lakes. It also can affect the taste of groundwater used for drinking.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

In the Twin Cities, the major culprit of chloride pollution is road salt used to melt ice in the winter. But in smaller cities and rural areas, chloride from wastewater plants is often a bigger source.

About 15 Minnesota wastewater treatment plants already need to reduce their chloride discharge levels in order to meet state limits. The city of Morris recently built an $18 million plant that centrally softens drinking water to reduce or eliminate the need for individual softeners in residents' homes.

But about six other cities want more time to meet chloride limits. Avon, population of about 1,600, is the first to be considered.

The federal Clean Water Act includes the option of granting a variance if a city's situation meets several criteria. Among them: If the process to reduce chloride discharge would cause "substantial and widespread economic and social impact."

Elise Doucette, a policy specialist with the MPCA, said this is one of the few times regulators can consider a city's ability to pay when deciding how quickly it must meet an environmental rule.

"Variances allow for a little bit of flexibility when you have that hardship issue," she said.

Dealing with chloride is a "really vexing problem" for communities, said former MPCA commissioner John Linc Stine, who now leads the nonprofit Freshwater Society.

"Strictly complying with the standard would require treatment that would be largely unaffordable and unattainable without massive infusion of governmental assistance," he said.

Stine said the sources of chloride vary from community to community, and so do the methods to address them. He called the variance process a "rational next step" to see if cities can meet the standards through measures tailored to their situations.

"If they can, then that's a helpful step forward, rather than using brute force," Stine said.

In Avon, the city's drinking water comes from wells that draw groundwater, which naturally contains minerals such as magnesium and calcium. Those minerals cause "hard" water that can leave spots on dishes and make clean laundry feel stiff.

In-home water softeners remove those minerals using a process called ion exchange, but leave behind a salty water mixture that ends up going down the drain.

In Avon, it goes to the city's wastewater treatment plant, which isn't designed to remove chloride. The treated water is then discharged into Spunk Creek, which eventually joins the Mississippi River.

Avon could install a reverse osmosis system to remove chloride from the wastewater, or centrally soften its drinking water with lime before it's piped to homes and businesses. Either solution would cost millions of dollars.

Jon Forsell, Avon's public works director, said that's more than his small city can afford on its own.

"People wouldn't come to Avon to live," Forsell said. "Taxes would be way too high."

If the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency approves a variance, it isn't just a free pass, Doucette said. The city would have time to evaluate its options, but also would need to take steps to reduce its chloride pollution during that 15-year period.

"They cannot get worse. They must get better," she said.

Avon also could address its chloride problem by educating residents to replace their old water softeners with high-efficiency models — and program them to use less salt. Aaron Neubert, general manager of Sterling Water Culligan in Sauk Centre, about a half-hour west, sees that as a real possibility.

"If we could really get in there to each home and inspect it and just make sure they're optimizing things, I think they can see the impact real fast," Neubert said.

The public comment period on Avon's wastewater permit and the proposed extension ends Friday. The EPA will decide whether to approve it.

Dear reader,

Political debates with family or friends can get heated. But what if there was a way to handle them better?

You can learn how to have civil political conversations with our new e-book!

Download our free e-book, Talking Sense: Have Hard Political Conversations, Better, and learn how to talk without the tension.