'We're targeted': Duluth confronts issue of missing Native women as state task force meets

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Shawn Carr has lost count of how many times he’s seen the surveillance video, studying every detail.

Sheila St. Clair walks up the stairs of her Duluth apartment building, talking to an unidentified man in a white tank top. She turns to him to say something — Carr doesn’t know what, there's no audio — before she follows him up the stairs.

She never comes back down.

Her friends think St. Clair was heading to the White Earth Reservation, but she never made it. She was reported missing a few weeks after the video was taken, and at first the tips flowed in. But that was four years ago.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

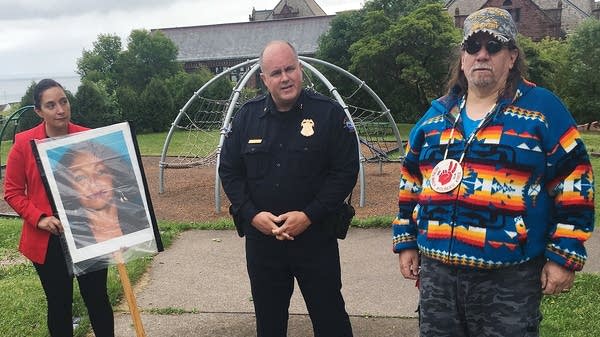

“Sadly this has become an annual event,” Carr, a member of the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Tribal Community, said Friday on the Central Hillside in Duluth at a press conference with city police. "I personally have been doing this to keep Sheila's name in the media so the case doesn't go entirely cold. Sheila's family and community miss her and we really want her back."

St. Clair has become the symbol of a broader epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women in northern Minnesota and across the state. Despite making up less than 1 percent of the Minnesota population, homicide rates for Native American women in the state were seven times higher than for white women between 1990 and 2016, according to the Minnesota Department of Health.

A new task force, set to hold its first meeting Thursday, will spend the next year digging into the underlying factors and systemic causes that explain why higher levels of violence occur against Native American women. They'll make recommendations to the Legislature next year to try to reduce and prevent violence where it is happening.

But Duluth and the surrounding area have been grappling with the issue for years. The Twin Ports of Duluth and Superior, Wis., have long been a hub of international sex trafficking, which disproportionately impacts Native women. The ports are connected to the Atlantic Ocean through the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and together are considered the largest freshwater port in the world.

Duluth also has a large Native community, which makes up roughly 2 percent of the city's population. The Fond du Lac Reservation is just 30 miles west of Duluth, but there are members of every tribe who reside in the city.

Duluth Mayor Emily Larson said she first learned about the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women on her second day in office four years ago. She held a press event on sex trafficking in the region.

"I had been kind of socialized in my previous work as a city councilor and as a community member to think that used to happen, that doesn't happen anymore. That used to be on the ships, that doesn't happen anymore. We live in a different kind of era,” she said. “I was appalled to find out that not only is it happening, but it never stopped."

The invisibility of the issue is part of the problem. Native communities say their disappearances don't get the same attention from the media and law enforcement that crimes involving other communities do. Groups point to the 2017 case of Savannah LaFontaine-Greywind, a Native woman who was eight months pregnant when she was lured into a neighbor’s Fargo, N.D., apartment to do a sewing project. Her neighbor murdered her and took her baby, tossing Greywind’s body in the Red River, where she wasn’t found for days.

"If this were white women, we would have legislation, we would have steep penalties, we wouldn't be talking about a task force. We'd be way past that already, and the fact that we're not is appalling,” Larson said. “These are not women who are taking leave of their life — they are gone. It's terrifying."

Trafficking through the ports is still a problem, but it's gone down since security increased after 9/11. Trafficking now tends to happen in more conventional ways, according to law enforcement. Social media plays a big role, but Native women are also drawn in through people they know.

“Some are people coming out of Chicago that are trafficking girls and women. Some are their own community members, which is fairly typical,” said Sheila Lamb, a Cloquet, Minn., City Council member who is serving on the task force. “I’ve had teens come to me and express fear — fear of traveling by themselves anywhere.”

The issue goes beyond trafficking. Native women are twice as likely to be sexually assaulted as women of other races, according to federal data. They are also subject to high rates of intimate-partner violence and other forms of violence. These factors, along with poverty, substance abuse and homelessness, make them far more likely to be exploited.

"I hear that it's because we're vulnerable, but it's because we’re targeted,” said Alicia Kozlowski, a member of the Fond du Lac Band who is going on her sixth month as a community relations liaison for the city of Duluth. “Social, economic and political status, look at poverty rates, homelessness, mental health. We face them."

Duluth Police Chief Mike Tusken has been an officer in the city for nearly three decades. He said the biggest challenge for police is building trust within the community.

"If our people who are indigenous in our community don't believe that the police department serves them, that it's not their police department, there is going to be delays in reporting and underreporting. And if there's distrust — if you're not an ally, you're an adversary."

In June, Carr said a group called the Gitchigumi Scouts was on a patrol to track down missing Native women when they discovered the body of Wahbinmigisi "Pennie" Robertson on the Fond du Lac Reservation. Her death was ruled a suicide, but the community believes it was a homicide and that law enforcement should have investigated further.

Tusken said he’s been working to build trust in Duluth. The police have followed every lead on St. Clair’s whereabouts, and there’s a $1,000 reward for any information that could lead to her or help police prosecute someone in her disappearance. They still consider her disappearance suspicious. A detective keeps a picture of her on his desk.

“He looks at her every day,” Tusken said.

Underreporting and lack of data make it impossible to get a handle on how widespread the issue really is. A recent study by the Urban Indian Health Institute revealed that only 116 of the 5,712 cases of murdered or missing Native women were logged into the Department of Justice’s nationwide database. Seventy percent of those declined cases were due to lack of evidence.

Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan, a member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, hopes that the task force will tackle best practices for law enforcement in handling every case that comes in and tracking them into the future.

“This is personal for me,” she said. “As the mom of a 6 1/2-year-old Native girl, if, God forbid, anything ever happened to her, I want her to be treated with kindness and care and urgency that anyone should expect if that kind of trauma happens to their family.”

But Flanagan and others in the community have hope. Awareness about the issue is increasing in movements across the nation. A national billboard campaign to raise awareness about the issue recently landed in Duluth.

Flanagan said it’s all because of the work of Native women.

“People always ask, ‘Why is this happening now?’ Dominant culture and non-Native people are starting to see what we’ve always known: Native women are leaders and matriarchs and have a real dedication to families and community,” Flanagan said. “It’s about time that the rest of folks catch up.”

MPR News reporter Dan Kraker contributed to this story.