How to spot (and fight) election misinformation

Misinformation and disinformation, especially online, continue to play a huge role in the 2020 election. Learn more about the types of false information you’re likely to come across this year — and how you can help fight it.

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

By Cynthia Gordi Giwa, ProPublica

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s User’s Guide to Democracy, a series of personalized emails that help you understand the upcoming election, from who’s on your ballot to how to cast your vote.

Summary:

Disinformation is deliberately created with the intent to cause harm, while misinformation is incorrect information shared by people who believe it to be true.

In 2020, dis- and misinformation about voting are very common online, especially about mail-in and in-person voting.

Fabricated content usually tries to play to your emotions. Always double-check images and news articles before you react or share them.

There’s an important pitfall to look out for this election season: misinformation. This kind of stuff shows up in the form of Facebook pages impersonating candidates, sketchy digital campaign ads and fabricated news content designed to deceive. Each and every piece of misinformation can have major consequences. Perhaps you’ll recall, a year and a half after President Donald Trump was elected, Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee released thousands of Facebook and Instagram ads placed by Russian operatives to interfere in the 2016 election.

To better understand the universe of misleading political information, and how to know it when you see it, we talked to Claire Wardle, executive director of First Draft News, an organization of social newsgathering and verification specialists dedicated to fighting mis- and disinformation online. (First Draft is also a partner in ProPublica’s Electionland project, helping us search the internet for content that could interfere with people’s voting!)

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

What are the different kinds of false information online?

First, a clarification of terms:

Disinformation is false information that is deliberately created and shared by people to knowingly cause harm — like, say, Russian actors trying to meddle in a U.S. election.

Misinformation is also false information, but the people sharing it don’t realize it’s fraudulent — like, say, your uncle sharing a questionable image on Facebook. Systematic disinformation campaigns, then, are able to use social media to directly target users who go on to accept and share the message.

First Draft has classified seven distinct types of mis- and disinformation swirling around our information ecosystem, from satire or parody to fabricated or manipulated content:

As we saw in the 2016 presidential election, some disinformation is driven by foreign governments or organized nonstate actors in order to interfere with an election. “We think a lot about countries like China, Russia or Iran who might be doing this for political reasons,” Wardle said.

Top trends in online election misinformation and disinformation

Here are some of the biggest themes First Draft is seeing this year:

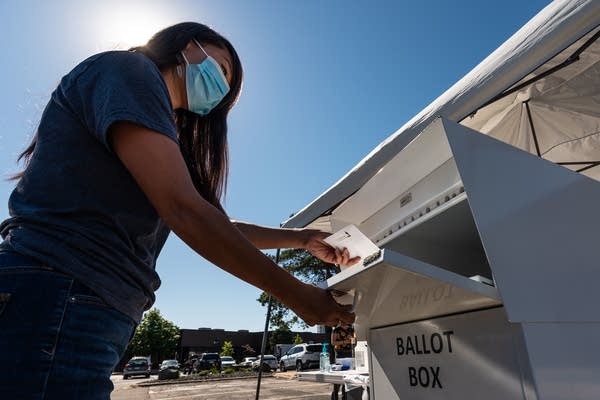

Making people question the safety of mail-in voting. “We know that we will see photos online of what looks like ballot boxes in strange places — ballot boxes ripped open, ballot boxes in the back of vans,” Wardle said. “Basically fueling rumors that mail-in voting is not going to be safe.”

Encouraging people not to vote because the process is too complicated. “We are seeing a lot of content trying to undermine the mail-in voting process — deliberately confusing ballot applications with actual ballots or pushing the idea that people need to send in their ballots weeks ahead of deadlines to make it count,” Wardle said of attempts to weaponize the additional steps needed to vote by mail. “The idea is to make people think it’s too complicated to bother voting this year, and the message coming across is that it’s not worth it.”

Scare tactics about the hygiene of polling places. “There’s this idea of, ‘If you go to a polling place, you might get harassed and spat on, or people haven’t washed their hands,’” Wardle said. “Things that are spreading fear by saying, ‘If you vote, you will get the virus.’”

How can I tell what election information to trust?

Here are some tips and tools that can help you assess content online.

If you see an image claiming to be proof of voter fraud: Run a reverse image search on Google. Go to images.google.com, click the camera icon and upload the photo. “You might find that it’s a real ballot box, but it’s from Kenya or Brazil. Often it’s genuine, but it’s used in a different context,” Wardle said. “You might see that it’s been debunked by PolitiFact or somebody else who has already gotten out there to say, ‘No, this is false.’ A reverse image search will also reveal whether a photo has been photoshopped by pulling up all similar images and allowing you to identify suspicious variances.

If you see a particularly dramatic political article from a news site you’ve never heard of before: Does it have an About Us page? Does it have a mailing address at the bottom? Does it have a Wikipedia page? These are some markers of real news sites that you’ll want to look out for.

Practice emotional skepticism: Many of us are susceptible to fabricated content because of our emotions and the way they interact with our biases. “It doesn’t matter how educated you are; it doesn’t matter whether you’re left or right,” Wardle said. “We’re vulnerable because as humans we’re drawn to information that reinforces our worldview. We want to consume information that makes us say: ‘Yeah, that’s what I thought. I’m right.’ So what that means is we’re really bad at taking on different types of information and we resist them.

“When you’re reading information, if it makes you angry or makes you want to share it with your best friend immediately, then recognize that you are having a visceral response to something. And in the moment, the part of the brain that is critical is not working,” Wardle said. “If you have that reaction, just slow down because your brain hasn’t caught up with your heart.”

For example…

Here are a few instances ProPublica and our partners have spotted over the years:

Numerous Facebook accounts sharing “outright lies” about voting by mail.

An image circulating on Twitter appearing to show an immigration officer arresting someone in line to vote, which was determined to be a hoax.

A YouTube video compilation claiming to show Democrats stuffing ballot boxes — videos that were all actually filmed in Russia.

Tweets that promote wrong information about the voting process, such as nonexistent voter ID requirements.

Help us help the election

As we mentioned before, Electionland is a coalition of newsrooms across the country that have banded together to help report on issues keeping people from voting in the election. Mis- and disinformation is just part of it. From now through Election Day, you can tell us about voting problems in your area.