New census data will shake up Minnesota politics

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Thursday afternoon the Census Bureau finally releases detailed information from the 2020 census, which will show how Minnesota has changed over the past decade, and also impact how political power and government spending will be distributed over the next decade. Here’s what to look for.

What’s getting released?

The Census Bureau is releasing detailed population counts covering geographies from states down to individual blocks, along with intermediate areas such as cities, counties and congressional districts.

The data released Thursday won’t be very accessible for ordinary Americans, however. Most of it is being released in a very technical and complex data format to fulfill the needs of state governments for drawing new legislative districts. The Census Bureau says it will release data in more user-friendly formats in coming weeks. In the meantime, news organizations including MPR News are planning to break down the key insights from Thursday’s release.

Where are all the extra Minnesotans?

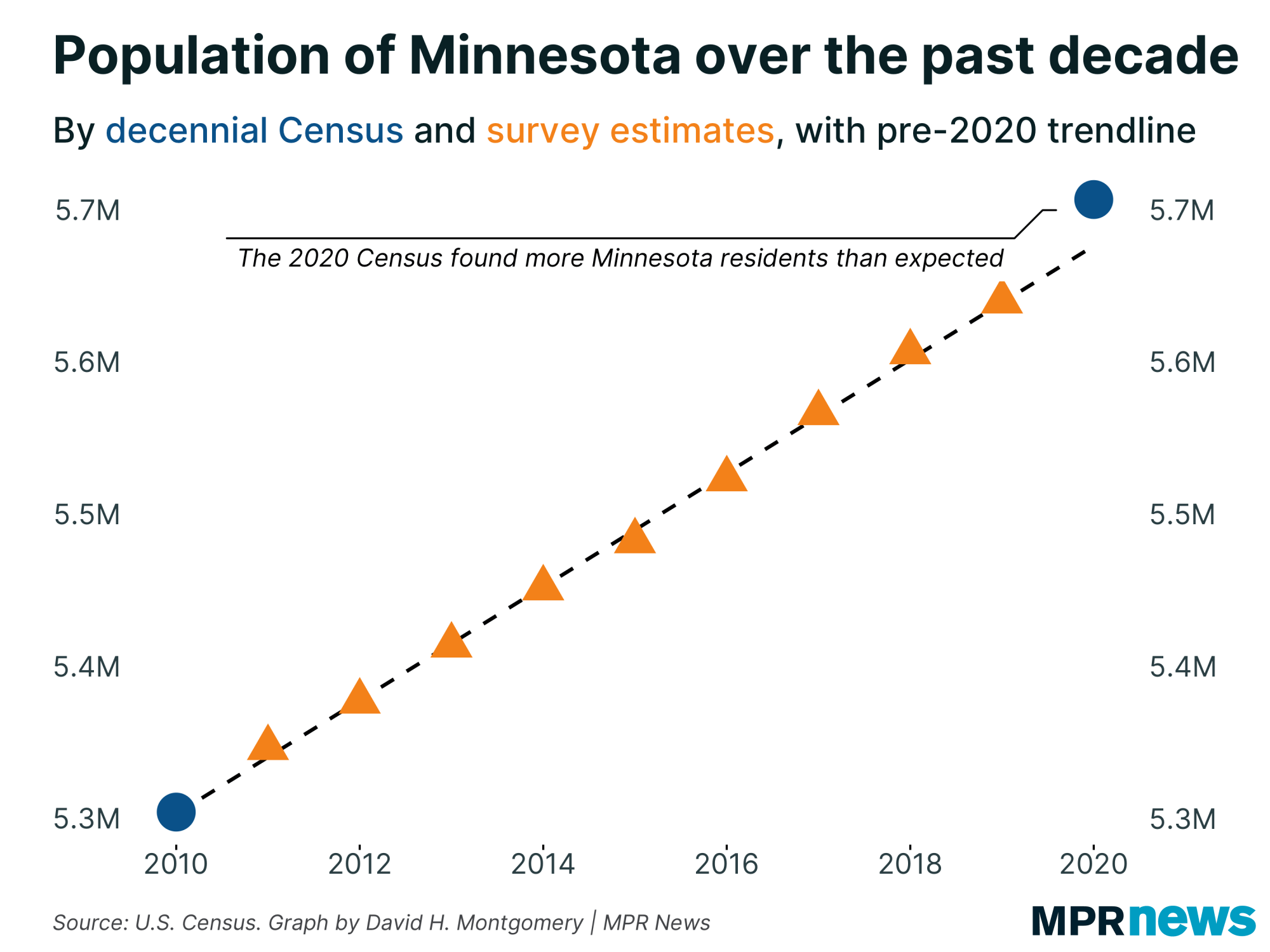

Earlier this year, the Census released one big number for Minnesota: its official 2020 population of 5,706,494 people.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

That was a little more than had been expected, which helped Minnesota keep its eight congressional seats by the skin of its teeth. Had the Census counted 89 more New Yorkers, or just 26 fewer Minnesotans, Minnesota would have lost its last seat to New York.

The latest census data will be below the state level. This will show us where Minnesota’s unexpected population growth came. For example, over the past decade, the seven counties in the core Twin Cities metro area have been growing steadily, while greater Minnesota has been largely flat overall. Did the metro grow even faster than had been expected? Or are there more people in greater Minnesota than demographers thought?

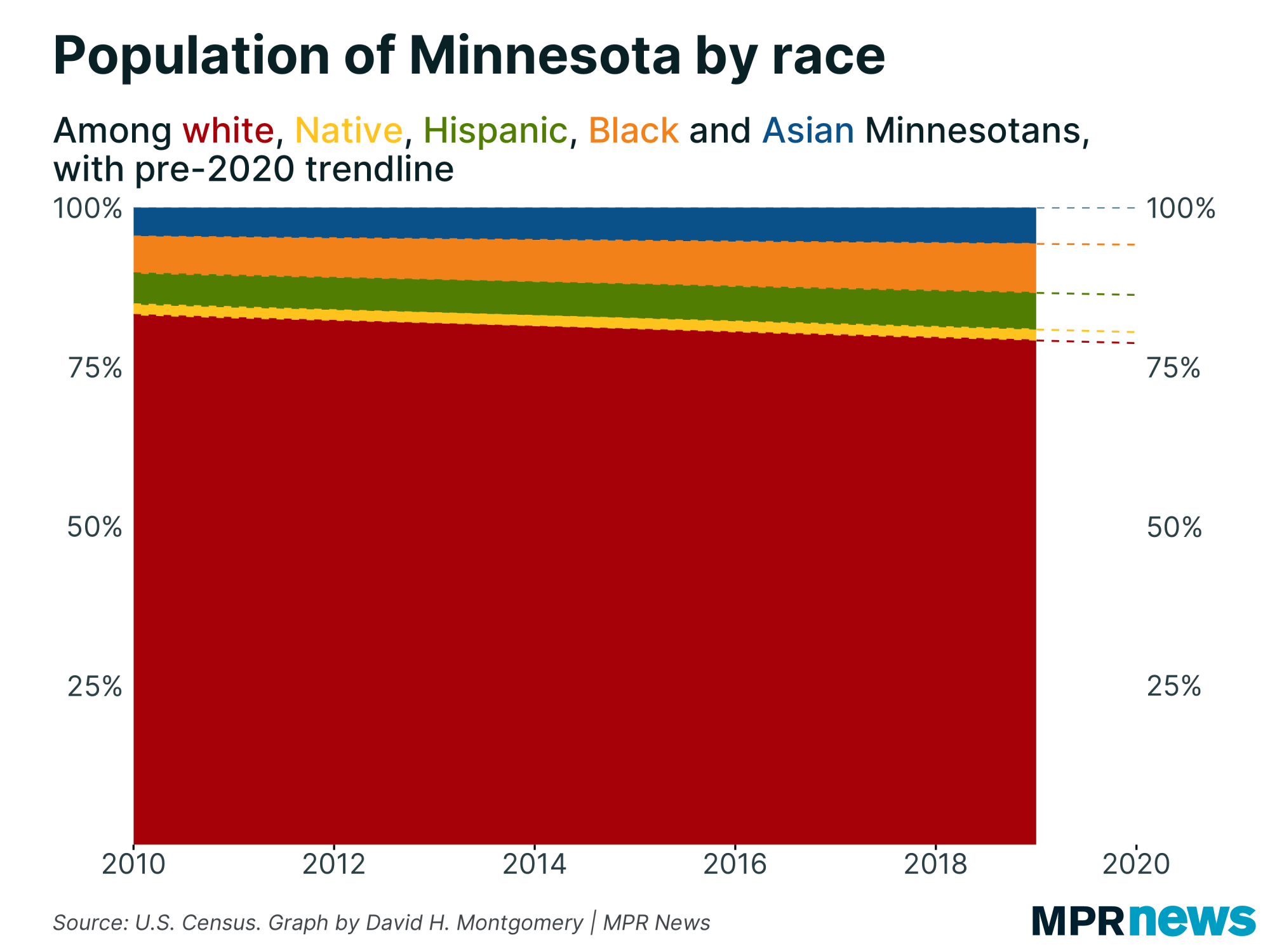

Another key question relates to Minnesota’s rapidly diversifying population. In 2010, about 83 percent of Minnesotans were non-Hispanic whites. The 2020 count will likely be 79 percent or below, based on survey research over the past decade. Meanwhile the Black population has risen nearly 2 percentage points, and the Asian and Hispanic populations just under 1 percentage point each. The final numbers will give firmer counts, along with more granular detail showing the relative diversity of Minnesota’s cities and counties.

Redistricting

The more concrete impact of the 2020 census numbers released Thursday will be for redistricting, the drawing of new districts for the U.S. House of Representatives and state legislatures. This is generally done every decade to adjust for changing populations and keep each district about the same size.

In Minnesota, the number of congressional districts and state legislative districts won’t be changing, so policymakers will have to adjust existing boundaries to equalize populations.

This is supposed to be a job for the state Legislature and governor. But because it’s possible to draw district maps that heavily favor one political party or another, Democrats and Republicans usually have not been able to agree on district maps for the state. With the Minnesota House under DFL control and the Senate controlled by Republicans, a stalemate is likely this year, too. That will likely mean the courts resolve an array of lawsuits by drawing their own map — as has happened in Minnesota in 2010, 2000 and 1990, and indeed every single redistricting here since 1966.

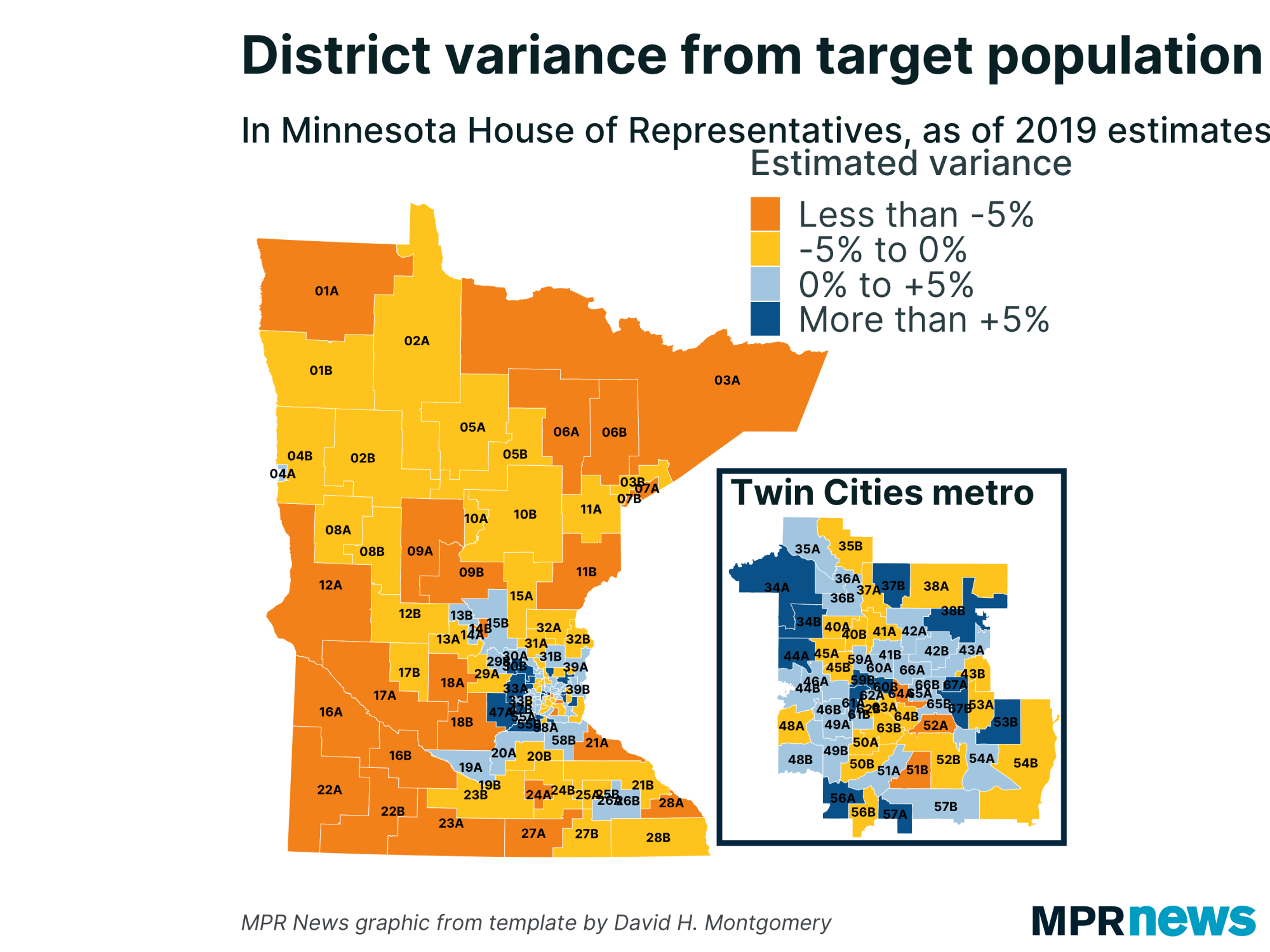

Whoever ends up drawing the maps, the primary need will be to move district boundaries to account for changing populations. Districts in fast-growing parts of the state have too many people and need to shrink. Districts in shrinking or slow-growing starts of the state don’t have enough people and will need to grow.

Estimated district population from recent surveys predict much of the Twin Cities metropolitan area now has too many people, especially the fast-growing western suburbs. In contrast, all but a few districts in greater Minnesota have too few people.

Once district lines are adjusted to equalize population, the net result will be a modest shift in political power to the Twin Cities metro. For example, the roughly 49,000 voters in Minneapolis’ District 60B currently get one representative in the state House, as do the 37,000 voters in southern Minnesota’s District 23A — the two most extreme districts by 2019 estimates. Redistricting will massively shrink those disparities, and give voters in fast-growing areas comparatively more weight in legislative elections.

This could end up helping the DFL, which tends to do better in the metro and worse in greater Minnesota — though not all growing districts are represented by Democrats and not all shrinking districts are represented by Republicans. Overall, Democrats hold 38 of the districts that as of 2019 estimates were too large, against 22 for Republicans. Among the too-small districts, Republicans hold 42 to Democrats’ 32.