Minnesota COVID surge creates dangerous ER bottlenecks

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Earlier this month, Paul Ulstrom's dad had his second stroke in a year. He was immediately taken to the emergency room in Chaska, Minn.

“We sat there for eight hours waiting for a room, which is really frustrating,” said Ulstrom.

Last year, when Ulstrom's dad had his first stroke during the most severe wave of COVID-19 to date, his care team found a bed faster.

This time, the wait was so long, Ulstrom says his dad was scared.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"There was a look in his face, and it breaks my heart because I could tell he was really worried,” Ulstrom said.

Finally, the Chaska hospital found a bed in St. Paul and Ulstrom's dad is stable now.

But what happened to Ulstrom and his father is a story playing out over and over again in emergency rooms around the state, and especially in smaller hospitals where there are few ICU beds to begin with.

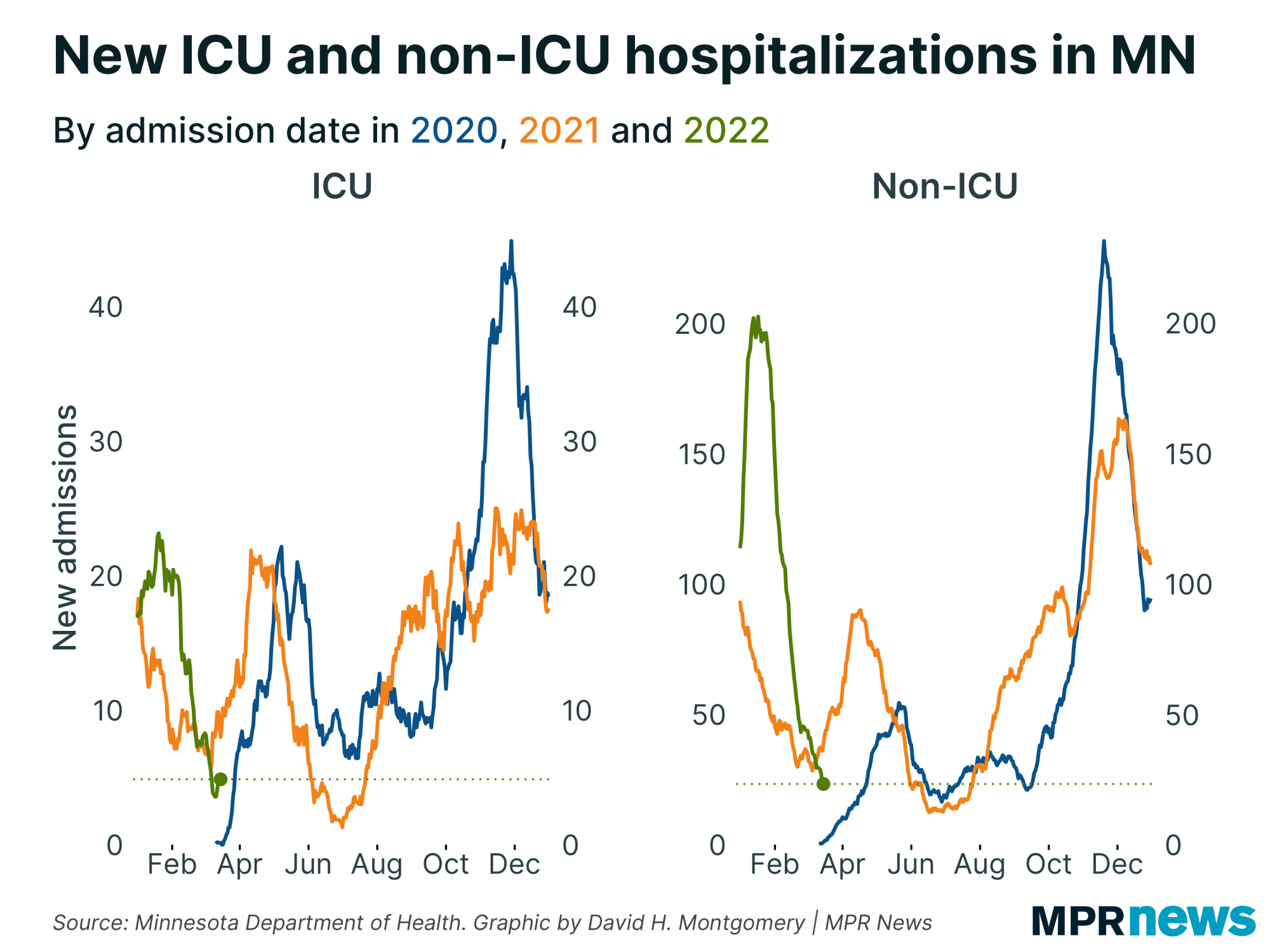

COVID hospitalizations have taken a sharp turn upward, a trend that health officials say could have been avoided if more people had been vaccinated. Staff shortages are contributing to a shortage of available hospital beds, too.

Patients coming in with non-COVID health issues — like strokes or heart attacks — are waiting hours and sometimes days in the ER while doctors scramble to find space for them at hospitals that can give them higher levels of care. Those delays are creating a dangerous situation for patients.

“It really is a combination of everything coming together right now to create a really difficult situation for health care in Minnesota,” said Dr. Monte Johnson, who is the vice president of medical affairs at St. Francis Regional Medical Center in Shakopee.

‘A huge bottleneck’

Recently, a patient arrived at Saint Gabriel Hospital's emergency room in Little Falls, complaining of a headache and confusion.

“We knew she had this brain tumor, and it was causing swelling,” said Dr. Dayle Quigley, who treated the patient. The woman needed brain surgery, fast — something Quigley’s small, critical access hospital couldn’t provide.

So she picked up the phone.

“We called 23 hospitals and were basically just told that there were no beds,” she said.

By the time the patient was transferred to a higher level of care that night, Quigley said the woman’s condition had deteriorated. She's not sure what happened to the patient.

Even in last fall’s COVID-19 surge, Quigley said it wasn’t nearly so hard to find a bed. And even though her hospital has a two-bed ICU that’s been expanded to six beds during the pandemic, there’s no room there for patients who would otherwise be quickly admitted because they are filled with COVID-19 patients who often stay much longer than the average patient.

“So a bed that, over six weeks, might typically take care of 15 patients is now able to take one patient,” she said.

‘I’ve never seen anything like this’

In Grand Rapids at the Grand Itasca Clinic and Hospital, emergency room medical director Dr. Paul Palecek says this phase of the pandemic is unprecedented in terms of how busy his ER is.

"I've been in practice 20 years, and I've never seen anything like this. It’s worse than the last surge,” he said. “Our boarding times are longer. We're just routinely facing situations where there is not a bed in the state to put a patient [in]."

He says most COVID-19 patients coming to his hospital for care are younger and unvaccinated.

On any given day, they have between 24 to 28 staffed hospital and ICU beds combined, all of them full. And right now roughly half are full with COVID-19 patients.

With no space at their hospital — and no space elsewhere — Palecek said ER staff are providing the best care they can, but it's not ideal. Sometimes that means sending patients home who would otherwise be admitted.

“Prior to COVID, we never would have established a patient newly on home oxygen and [then] send them home straight from the emergency department. And now that's commonplace,” he said.

Palecek said his staff is not doing anything unsafe — they still consult with their specialist care teams before deciding how to treat incoming patients — but, as front-line physicians, they're often practicing beyond their training.

“Still, in reality, the actual implementation of that care is falling to the emergency department physician alone,” he said.

Avoidable situation

In the Allina Health system, which includes rural hospitals in central and western Minnesota, 72 percent of the system's hospitalized COVID patients are unvaccinated.

Johnson, whose Shakopee hospital is part of Allina, said this latest surge could have been avoided if more people had been vaccinated against the virus.

“We know that getting vaccinated against COVID is tremendously helpful in keeping patients from getting sick enough with COVID to end up in the hospital,” he said. “The vaccines are very, very effective at keeping people out of the hospital.”

Ulstrom said that a year ago, when his father had his first stroke, he understood why it took a while to find his dad a bed. But this time, he feels differently.

“My frustrations are similar but not the same,” he said. “[A] year ago, vaccines weren't available yet."

If more people had gotten vaccines, his dad wouldn't have had to wait so long for care, said Ulstrom.