Twins legends Oliva, Kaat among six elected to Baseball Hall of Fame

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: 8:50 p.m.

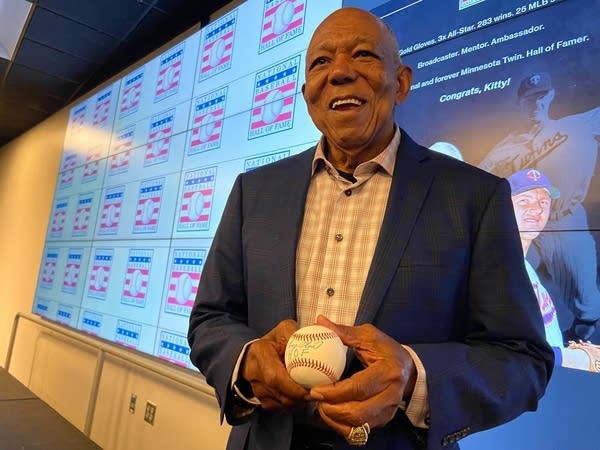

Former Minnesota Twins teammates Tony Oliva and Jim Kaat were among six players elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday by a pair of veterans committees.

They were joined by Buck O’Neil, a champion of Black ballplayers during a monumental, eight-decade career on and off the field, as well as Gil Hodges, Minnie Miñoso and Bud Fowler.

Oliva and Kaat, both 83 years old, are the only living new members. Longtime slugger Dick Allen, who died last December, fell one vote shy of election.

"Now they call me Hall of Fame, it's nice to be in this group,” Oliva said on Monday as he celebrated his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame, “but I think for me, I've been in that group a long time — to be here in Minnesota, and have those great people around me, my family, and that is most important for me."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The six newcomers will be enshrined in Cooperstown, N.Y., on July 24, 2022, along with any new members elected by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. First-time candidates David Ortiz and Alex Rodriguez join Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling on the ballot, with voting results on Jan. 25.

Passed over in previous Hall elections, the new members reflect a diversity of accomplishments.

Oliva was a three-time AL batting champion who spent his entire 15-season career with the Twins.

The Cuban-born outfielder known for hitting wicked line drives was the 1964 AL Rookie of the Year, and was an eight-time All-Star. After his playing career was cut short by knee problems, he was a coach for the Twins — including for Minnesota's two World Series-winning teams. He's also been an analyst on the Twins' Spanish radio broadcasts for more than 15 years.

“I was looking for that phone call a long time,” Oliva said on MLB Network. “I had so many people work so hard for me to be elected. They said I should have been elected 40 years ago. To be alive to tell the people means a lot me."

Kaat was 283-237 in 25 seasons and a 16-time Gold Glove winner. He pitched in four decades and won a World Series ring as a reliever on the 1982 Cardinals.

He was an original member of the Twins when they moved to Minnesota from Washington in 1961. He spent all or part of 13 seasons in Minnesota. He was a three-time All-Star in his career, and after retirement worked as a sports broadcaster.

“I never thought I was the No. 1 pitcher,” he said. “I wasn’t dominant. I was durable and dependable. I am grateful they chose to reward dependability.”

Previous Minnesota Twins elected to the Hall of Fame are Harmon Killebrew (1984), Rod Carew (1991), Kirby Puckett (2001) and Bert Blyleven (2011).

This year was the first time O’Neil, Miñoso and Fowler had a chance to make the Hall under new rules honoring Negro League contributions. Last December, the statistics of some 3,400 players were added to Major League Baseball’s record books when MLB said it was “correcting a longtime oversight in the game’s history” and reclassifying the Negro Leagues as a major league.

“Jubilation,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, that O’Neil helped create, after the voting results were announced.

O’Neil was a two-time All-Star first baseman in the Negro Leagues and the first Black coach in the National or American leagues. He became a remarkable ambassador for the sport until his death in 2006 at 94 and already is honored with a life-sized statue inside the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

For all O’Neil did for the game his entire life, many casual fans weren’t entirely familiar with him until they watched the nine-part Ken Burns documentary “Baseball,” which first aired on PBS in 1994.

There, O’Neil’s grace, wit and vivid storytelling brought back to life the times of Negro Leagues stars Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell, plus the days of many more Black ballplayers whose names were long forgotten.

Kendrick said it was too bad O’Neil won’t be in Cooperstown for the induction ceremonies next July 22, “but you know his spirit is going to fill the valley," he said on MLB Network.

Miñoso was a two-time All-Star in the Negro Leagues before becoming the first Black player for the Chicago White Sox in 1951. Born in Havana, “The Cuban Comet” was seven-time All-Star while with the White Sox and Indians.

There was nothing mini about Saturnino Orestes Armas Miñoso on the field. He hit over .300 eight times with Cleveland and Chicago, led the AL in stolen bases three times, reached double digits in home runs most every season and won three Gold Gloves in left field.

Miñoso finished up, or so it seemed, in 1964. He came back at age 50 for the White Sox in 1976 — going 1 for 8 — and batted twice in 1980, giving him five decades of playing pro ball.

The White Sox retired his No. 9 in 1983 and he remained close to the organization and its players before his death in 2015.

Fowler, born in 1858, is often regarded as the first Black professional baseball player. The pitcher and second baseman helped create the popular Page Fence Giants barnstorming team.

Hodges became the latest Brooklyn Dodgers star from “The Boys of Summer” to reach the Hall, joinng Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella and Pee Wee Reese.

An eight-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glover at first base, Hodges enhanced his legacy when he managed the 1969 “Miracle Mets” to the World Series championship, a startling five-game win over heavily favored Baltimore.

Hodges was still the Mets’ manager when he suffered a heart attack during spring training in 1972 and died at 47.

O’Neil and Fowler were selected by the Early Days committee. Hodges, Miñoso, Oliva and Kaat were chosen the by the Golden Days committees.

The 16-member panels met separately in Orlando, Florida. The election announcement was originally scheduled to coincide with the big league winter meetings, which were nixed because of the MLB lockout.

It took 12 votes (75 percent) for selection: Miñoso drew 14, O’Neil got 13 and Hodges, Oliva, Kaat and Fowler each had 12. Allen had 11.

O’Neil played 10 years in the Negro Leagues and helped the Kansas City Monarchs win championships as a player and manager. His numbers were hardly gaudy — a .258 career batting average, nine home runs.

But what John Jordan O’Neil Jr. meant to baseball can never be measured by numbers alone.

O’Neil became the first Black coach in American League or National League history with the Chicago Cubs and enjoyed a prolific career as a scout.

His impact is visible to this day.

Along with his statue in Cooperstown, the Hall's board of directors periodically present the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award to a person whose “whose extraordinary efforts enhanced baseball’s positive impact on society ... and whose character, integrity and dignity” mirror those shown by O’Neil.

In 2006, it appeared O’Neil would get to soak in the praise earned for his work when the Special Committee on Negro Leagues convened to study candidates for the Hall of Fame. The panel indeed elected 17 new members but O’Neil was not among them, narrowly missing out.

O’Neil was chosen to speak on behalf of those 17 newcomers, all deceased, on induction day at Cooperstown. True to his nature, he didn’t emit a single word of remorse and regret about his own fate of being left out.

Two months later, O’Neil died in Kansas City.