Minnesota rural hospital workers feel the strain as colleagues leave, COVID stays

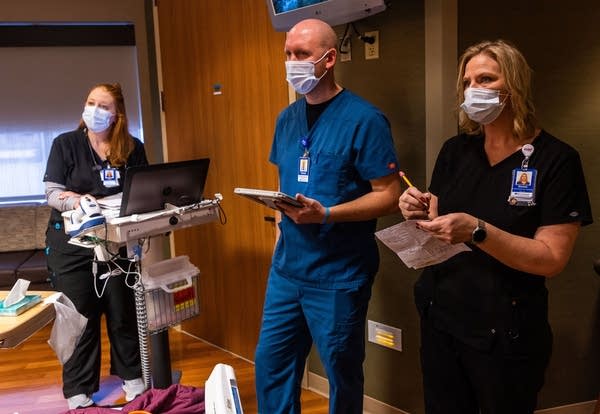

Registered nurse Lisa Streadwick (left), pharmacist Travis Sporre and nurse supervisor Donna Corey listen to feedback from patient Kathryn Lathrop on Feb. 2 during an early morning huddle at Riverwood Healthcare Center in Aitkin, Minn. The early morning huddles are conversations between health care providers and the patient allowing for all care parties to be on the same page and for the patient to provide feedback.

Derek Montgomery for MPR News

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.