Jury finds Minnesota man guilty on all counts in fentanyl overdose case

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: March 31, 4:06 p.m. | Posted: March 30, 4 a.m.

A federal jury on Thursday convicted a Hopkins, Minn., man in connection with the opioid overdose deaths of 11 people across the country.

Federal prosecutors said customers of Aaron Broussard purchased what they thought was 4-fluoroamphetamine, or 4-FA, a stimulant that’s similar to Adderall. Instead, the 31-year-old man allegedly sent them fatal doses of fentanyl.

The jury returned guilty verdicts on all 17 counts, including distribution of fentanyl resulting in death. That charge alone carries a 20-year mandatory minimum sentence.

David Masik of Racine, Wis., whose 25-year-old daughter Devon Masik died of an overdose, said after the verdict that after six years, his family finally has some closure.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

“There was so much information, so many witnesses, so many documents, and it was such a convoluted mess and they really just pulled everything together, very concise, very coherent,” Masik said, praising the work of federal prosecutors in the trial. “They did a really great job.”

Aaron Morrison, Broussard’s defense attorney, focused on the medical evidence and urged jurors to question it. He said in his closing arguments Wednesday that many of the autopsy reports never mentioned fentanyl. He also questioned whether it was his client’s fentanyl caused the 11 deaths.

Morrison also argued that 4-FA is not on the list of controlled substances.

Obviously, the jury did not agree with that. Morrison declined to comment on the verdict Thursday.

Broussard has been jailed since he was first charged in late 2016. He’s expected to remain in the Sherburne County Jail pending his sentencing.

Scott Beimel was 46

Larry Beimel said the death of his brother, Scott, on April 17, 2016 came as a painful shock to their family.

“The medical examiner said it was a heart attack, and heart attacks do run in families,” his brother said.

Scott Beimel had three kids and a good job at a food processing plant about 90 minutes from Kane, Pa., the one-stoplight town where Scott and Larry grew up.

The brothers, a year apart, were close. As small children, they cut each other’s hair. When Larry was serving in Operation Desert Storm, Scott mailed him a steady stream of packages and letters.

“Everybody that met him loved him. He was the funniest guy,” Larry said.

Beimel said his brother did not struggle with opioid addiction. Their family received more shocking news from Scott’s life insurance company.

“We saw the word ‘fentanyl’ for the first time on insurance paperwork. We had no idea,” Larry Beimel said.

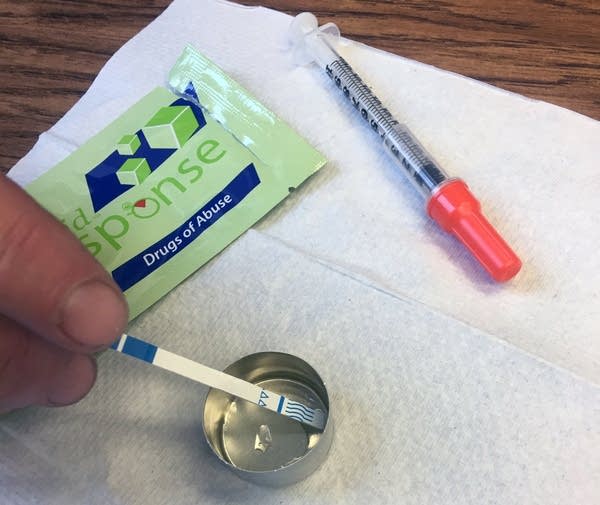

The family would learn much later that Scott Beimel had purchased what he may have believed was a stimulant from a website called plantfoodusa.net. But federal prosecutors allege that the owner of that website, Aaron Broussard, sent two grams of pure fentanyl instead.

At the time, the Beimels had no idea that they were among 11 families in the spring of 2016 to lose loved ones to a powerful painkiller allegedly mailed from an apartment in Hopkins, Minnesota.

She was ‘a light’

Devon Masik succumbed to fentanyl at age 25 the day before Scott Beimel died. David Masik described his daughter as “a light ever since she was born.”

Masik said Devon struggled with alcohol and had moved from Racine, Wis. to southern California to seek treatment and work on her interior design degree. Devon met a supportive partner who was also in recovery.

Masik said the couple went to the same website in search of an alternative to Adderall.

“She wasn’t looking for a high. She was looking to concentrate. She was looking to keep doing well in school. She was looking to have something natural that isn’t threatening to her sobriety,” Masik said.

Prosecutors say Devon’s partner also overdosed on the fentanyl but survived, as did five other people across the country alleged to have bought drugs from Broussard. In the room where Devon died, investigators allegedly found a slip of paper that said “PFUSA” in Broussard’s handwriting along with a pouch of white powder sent from suburban Minneapolis.

And then there was Jason Beddow.

Lucy Angelis says her husband, a 41-year-old agricultural economist at the University of Minnesota, was meticulous about getting home to the hobby farm they shared in Anoka County to feed their animals. Angelis says she became concerned when he didn’t respond to calls or texts.

“I knew something was wrong, because he wouldn’t have left the animals at home alone for that extended period of time,” Angelis said.

Beddow suffered a fatal overdose in his campus office.

As in the case of the Beimel family, investigators initially told Angelis that her husband had died of a heart attack. Four months later, a toxicology report determined that it was fentanyl.

In court last week, Broussard’s attorney Aaron Morrison said his client never knowingly sold fentanyl as the charges allege. He added that by selling what Broussard thought was an “analog” stimulant not on the controlled substance list, Broussard “believed he’d found a product that was on the right side of the law.”

But prosecutor Melinda Williams said that under the law “you don’t get a pass because you were mistaken about the drug you distribute.”