New map highlights home deeds with racist language in Ramsey County

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

A group working to identify and nullify racist language in Twin Cities property records is out with new data on Ramsey County. Researchers with the Mapping Prejudice project combed through reams of documents and found more than 2,000 homes that were off limits to people of color until the mid-20th century.

Racially-restrictive covenants have long been illegal, but supporters of the project say acknowledging past wrongs is the first step toward reversing Minnesota’s homeownership and wealth gaps, which are among the worst in the nation.

The new map came as a surprise to Etienne Djevi, who said that until this week he had no idea that the deed to his Roseville house likely includes a clause that once prohibited any non-white person from buying or renting it.

“I was shocked,” Djevi said. “I’m Black man. To be living in this house for two and a half years and to figure out that somebody in the past did not want my kind to be in here, it hurts.”

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Djevi, an infectious disease physician who grew up in Benin, shares his home with his wife and two sons. Though he has yet to see the records for himself, Djevi’s property is marked on a new map from the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice project, indicating that the parcel has a racially-restrictive covenant.

While the language can’t be removed from the title, Djevi said he’s contacting the group Just Deeds to have its volunteer attorneys add wording to renounce the racist clause “so that it’s not anything that maybe another Black person or another person of color will have to deal with in the future.”

Mapping Prejudice technical lead Michael Corey said the earliest-known covenant in the Twin Cities dates to 1910. In the following decades the practice grew at the behest of real estate agents and developers. Corey said covenants, often mentioned in housing advertisements, continued even after 1948, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the clauses unenforceable.

“Covenants were often put on these properties as a way to attract white buyers,” Corey said. “And unfortunately they didn’t think anything of throwing a lot of people out and under the bus to attract people to those properties.”

Since it started in 2016, Mapping Prejudice has identified more than 25,000 covenants in Hennepin County. For the last three years they’ve partnered with the Welcoming the Dear Neighbor? project at St. Catherine University on a similar effort in Ramsey County, where they’ve confirmed about 2,400 covenants so far. Corey said that’s likely a significant undercount because of missing or unreadable deeds.

He said the process begins by feeding microfilmed records through optical character recognition software, which looks for racist language. Anything the computer flags then goes to a group of volunteers. It’s a laborious process.

“Combined between Ramsey County and Hennepin County we’ve had over 6,000 volunteers work on this data,” Corey said

Cindy Schwie is among the group of volunteers. Like Djevi, Schwie lives in Roseville and said she became interested in the project after spotting “disgusting” language in the title abstract for the home that she purchased with her husband in 1974.

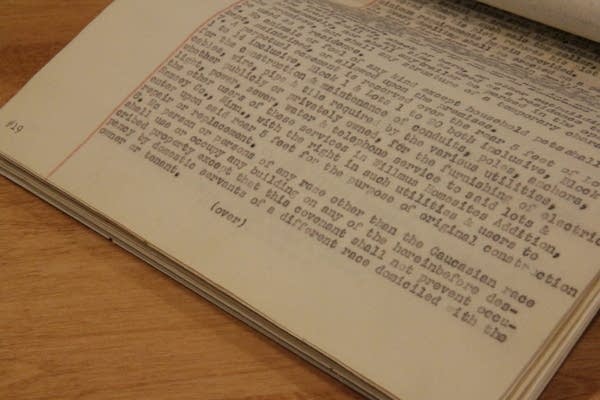

The clause says that “No person or persons of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building on any of the hereinbefore described property except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with the owner or tenant.”

Even though the clause has been illegal for decades, Schwie said she’s working to discharge it, in part to send a message to her home’s future owners.

“As homeowners, we do not want this on there,” Schwie said. “It’s not what we believe in. And we want other people to know in history that we did not believe in this.”

Carol Gurstelle lives near Schwie in a mid-century subdivision where all the homes have racially-restrictive covenants. Gurstelle said the clause on her property deed is specific and explicit; it bans “Negroes,” as well as Jews and people of Asian descent.

Gurstelle said she learned about the clause when she purchased the home nearly five decades ago. Gurstelle said she long considered it a curious bit of archaic legalese.

“Since then, with the rising awareness of prejudices in this country, and how practices such as racial covenants have shaped the way our cities have grown, I’m more offended by it now than I was then.”

Besides Roseville, the new map shows pockets of covenants scattered across St. Paul, Maplewood, White Bear Lake and other cities.

St. Catherine University sociologist Daniel Williams said the effort to identify restrictive covenants is not just about nullifying racist language. Its larger goal is to illustrate how the pernicious influence of that language remains.

“Segregation was not inevitable,” Williams said. “But once segregation happened, it did effectively racialize space, and that had consequences that were really never ending.”

Because covenants and other racist policies restricted homeownership, Williams said that Black people have had far fewer opportunities than others to build wealth and pass it to future generations. He points to a 2021 Federal Reserve study that pins the median net worth of white households in Minnesota at $211,000. For Black households, that figure is $0.