Why Dems rule the city -- Republicans, the outer ring

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

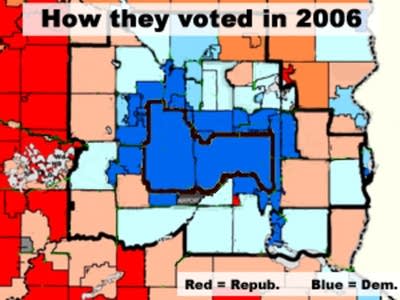

Knock on any random door in Minneapolis or St. Paul, and this poll says 77 percent of the time the person who answers will be a Democrat.

But if you hop in the car and hit the highway, the political map starts to shift.

As soon as you cross over city limits and into the suburbs, the percentage of Republicans rises dramatically. It pops from 8 percent in the city to 39 percent in the inner ring suburbs.

[image]

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"An inner suburb for this survey was a place that either borders a central city, or any place that borders one of those places," explains University of Minnesota demographer Thomas Luce.

So Edina would be an inner ring suburb, because it borders Minneapolis. And Eden Prairie would also be inner ring, because it borders Edina.

Everything beyond there we'll call outer ring, all the way to Young America Township, about an hour's drive from downtown Minneapolis.

And once you get to the outer ring, the politics shift even more; Republicans outnumber Democrats by a 10 point margin.

"It's as if the Republicans are a tribe and they're living in one part of Minnesota, and Democrats are another tribe living elsewhere," Humphrey Institute political scientist Larry Jacobs marvels. "It is one of the most striking manifestations of the polarization in our political world today. We are literally living apart."

But here's the big question: How did it get to be this way?

[image]

Is there something about breathing city air that turns you into a Democrat? Something about the suburbs that breeds Republicans?

Jacobs doesn't think so. His guess is: There's something about the city that attracts liberals, and something about the suburbs -- especially the outer ring -- that calls to conservatives.

"It's almost as if the Republicans are being drawn to the big blinking red light, as moths, whereas the Democrats are being drawn to the big, blinking purple light," Jacobs says.

Mike Beyer, mayor of the outer ring western suburb of Rockford, says it's obvious why conservatives would prefer his town to Minneapolis.

"Because you have your space," Beyer says. "You're not part of an apartment complex, which is a communal area. Communal to me is social, and social goes to socialism. But here, it's your space, your time, your business, and that's generally conservative people."

Susan Widmar lived in the suburbs for 13 years, but her liberal heart yearned for the day when she could afford to buy a nice a house in the city. And finally, four years ago, she and her husband made the move to St. Paul.

"We felt at home immediately," Widmar says. "And driving down Summit Ave., and seeing the protestors on the street corner, it was just like they were there for us -- to welcome us home."

Widmar likes the ethnic diversity of the city, and she feels good about burning less gas than she used to.

"The fact that we can walk two blocks and get a six pack of beer, and we can hop on the bus and go downtown is all really attractive to us," she explains. "We don't have to drive our cars around if we don't want to."

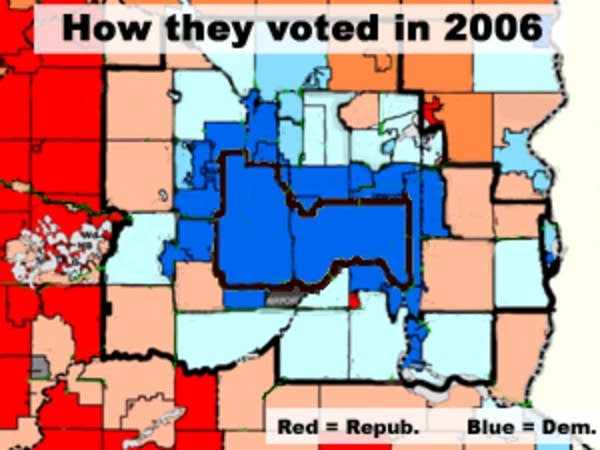

There are a number demographic differences that also might help explain the preponderance of Democrats in Minneapolis and St. Paul, proper. One is the racial breakdown. A third of Twin Cities residents are non-white, and minority groups vote overwhelmingly for the Democrats. The outer ring is 95 percent white.

[image]

The median household income in the central cities is also substantially lower than in the outer ring suburbs. In 1999, it was about $38,000 a year in the cities and $62,000 in the outer ring. Higher income folks tend to vote Republican.

Joel Kotkin, who studies cities and suburbs at Chapman University in California, says three or four decades ago, cities started losing middle-class white people with school-age children. Those families went seeking the schools, the space and the security of the suburbs. And that left cities with what Kotkin calls an array of demographic "niches."

"And that niche tends to be either minorities, poor people, young people, people without children -- all of whom tend to be vote much more liberal."

But the suburban picture isn't a static thing. The outer ring is growing like crazy, with a population that increased more than 10 percent between 1990 and 2003. And the inner ring is changing, too.

"The older suburban areas are becoming more stressed, more poor, more racially diverse, and more like the city than they are like newly developing suburbs," says former state Sen. Myron Orfield, DFL-Minneapolis, who now directs the Institute on Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota Law School.

Orfield has been studying those trends for more than a decade, and he says those demographic shifts have put one-time Republican strongholds up for grabs.

"Gore and Kerry won in Edina, narrowly, and people 20 years ago never thought that would have been possible," he says.

Kim Foster, 41, has recently noticed her inner-ring suburb turning blue. When Foster was growing up there, Minnetonka was predictably Republican. Now, it seems to be swinging to the left.

"I didn't realize it until just a few weeks ago when we had a neighborhood party," she says.

Foster explains that at some point conversation turned to the presidential race.

"I would say out of the 20-some people there, 17 I know for sure were Democrats." She says couldn't wait to get home and tell her husband about it.

"I truly believed the whole neighborhood was Republican," Foster says. "So, I'm floored by it."

The inner ring suburbs are still far from solid DFL territory.

The MPR poll put the inner ring at 54 percent Democrats, 39 percent Republicans. But people in those suburbs have a tendency to split tickets. Places like Bloomington, Inver Grove Heights, Coon Rapids and Maple Grove saw a lot of voters check boxes for both Republicans and Democrats in 2006.

Jacobs, the Humphrey institute political scientist, says that makes the inner ring a key battleground in this year's election.

Dear reader,

The trustworthy and factual news you find here at MPR News relies on the generosity of readers like you.

Your donation ensures that our journalism remains available to all, connecting communities and facilitating better conversations for everyone.

Will you make a gift today to help keep this trusted new source accessible to all?