U of M resumes nuns' Alzheimer's study

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

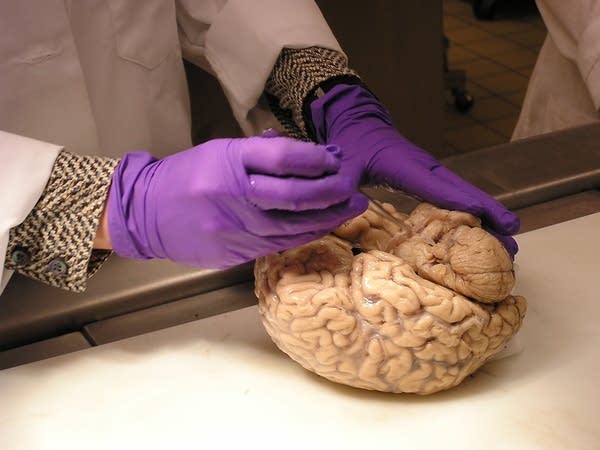

Dr. Karen Santa Cruz is leading a tour of the brain room.

"This is where we're storing the brains from some of the 670 sisters," said Dr. Santa Cruz, a neuropathologist, a fancy name for someone who studies brain diseases.

"This brain looks good. The bulges look good and the creases are narrow. So that's a healthy looking brain," she said as she examined one of the brains.

Santa Cruz already knows that about half the brains in this small storage room show signs of Alzheimer's disease or dementia, while the other half do not.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The early findings of the Nun Study were developed by David Snowdon. He began the study at the U of M in 1986. Four years later, he took a job at the University of Kentucky and moved the study with him.

Snowdon's early findings from the study were considered groundbreaking and drew widespread attention -- even landing the sisters on the cover of Time magazine. When Snowdon retired last year, the U of M won a bid to get the study back.

Since then, more new brains have arrived that still need to be examined. It's Santa Cruz's job to pick up where Snowdon left off.

"The most interesting people to study are the ones that have a lot of pathology in their brain, but they aren't demented for some reason," Santa Cruz said.

There are about 10 to 15 brains in the collection that appear diseased, but those particular sisters did not show outward signs of memory loss. Santa Cruz wants to figure out why, and she won't be going it alone.

As one of the conditions for returning the Nun Study to Minnesota, the U of M has agreed to digitally scan all of its tissue samples and make them available online to researchers throughout the world.

Dr. Kelvin Lim stands at the back of a vast temperature-controlled archive.

"[The brains] are sort of the wet records. We have the dry records up here in terms of paper records," said Dr. Lim, the new scientific director of the Nun Study.

In front of Dr. Lim are rows of boxes filled with medical and dental records, report cards and journals. Lim pulls a handwritten essay from a carton. The sister who wrote it was probably only 18 or 19 years old at the time.

"It says. 'January 11, 1893, I came to the home of my good parents who live on a farm near New Trier, Minnesota,'" Lim read.

The original research has already established a link showing that the more complex these early writings, the lower the risk of mental dysfunction and even disease or death among the sisters in the study, Lim said.

Lim's job is to look for even more evidence correlating early education with brain health.

The university will also continue testing the remaining 50 or so living sisters who are enrolled in the study.

"Some of the questions are hard to answer," said Sister Mary Louise Pihaly, 93, who lives in Mankato at the School Sisters of Notre Dame health care facility. "You had to use your memory a lot, and my memory isn't the best anymore."

Sister Mary Louise can't remember a lot of her fellow sisters' names anymore. But on the whole, she's doing remarkably well as she ages -- which she credits in large part to her personality and lifestyle.

"My dad called me Sunshine. And so I guess I had a more sunny disposition, and I read that that helps. And being active. And I am active. I keep busy," said Sister Mary Louise.

Her colleague, Sister Celine Koktan, who will turn 97 years old on Saturday, said she's at peace with the idea of donating her brain for science someday.

"The fact that I have not had any of this Alzheimer's disease, or even any inclination so far, is something that you know they would naturally want to study," she said.

The U of M is hoping to fund another study in a few years utilizing the sisters and their brains. Mankato's provincial leader Sister Catherine Bertrand suspects there will be a lot of interest among the sisters who couldn't sign up for the first study.

"In the first round, we had some that were just bitterly disappointed that they didn't make the age cut. They were too young. So yes, I think we would have probably another generation," she said.

U of M researchers hope a second study will lead to discoveries about other brain conditions, such as Parkinson's disease and stroke.