Artists ease the pains of recovery

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

On a Tuesday night, Pat Owen is leading a workshop for a group of patients and their families at Bethesda Hospital in St. Paul. It appears to be a simple project: tell a story by drawing a picture. Give it a title, and maybe a one sentence description. But for many here, drawing and writing are challenges - Bethesda Hospital treats patients with long term physical therapy needs - people who have suffered trauma from an accident, or are recovering from a stroke.

That's what brought Charlie Hogan here. Hogan had a severe stroke nine months ago. Tonight his daughter Casey sits with him, and they work together on an image of them walking in a park. It's a memory from a happier time.

This workshop gives families something to do together during their visits, and takes the focus off the patient's illness. It also engages the patient in basic communication skills and hand eye coordination. Owen is not a therapist, but there are nurses in the room, observing and helping out.

Bob Payton, Bethesda's Project Director and Therapeutic Recreation Specialist, is no newbie to the arts. He often brings his banjo into the hospital wards and plays for patients, singing Pete Seeger songs while folks tap along with their hands or feet. Payton said bringing artists into the healthcare system is helping to change the image of the hospital as an isolated, sterile place.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"In the midst of a place where there's often so much tragedy and loss and depression and sadness you can bring in a community artist and that artist can change that whole environment," said Payton, "and make it into something where people are smiling and laughing and moving their bodies around. That's powerful stuff."

Payton said there's little research quantifying the real benefit of integrating the arts in healthcare. But the studies which have been done have produced remarkable results. One study found after just an hour of engagement in an artistic activity, a patient will report being in a better mood, and say they aren't in as much pain.

That's why Payton's working with the non-profit Community Programs in the Arts - or COMPAS - to match artists with different hospitals and clinics. Artists like poet Richard Solly. Solly teaches creative writing and poetry at St. Joseph's hospital to a group of patients who suffer from both mental illness and addiction.

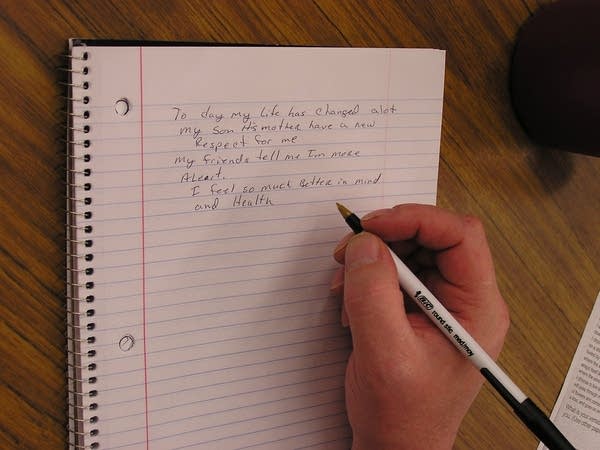

Solly said the people who come to his class to write poetry are sharing their stories, sometimes for the first time. He knows the writing is valuable to the healing process - he experienced it himself while in treatment for cancer. He said there are some things you can't tell another soul, but you can put down on a piece of paper. And at its best, writing can take your pain, and turn it into something beautiful.

"In the end I think that's what writing is all about," said Solly. "It's about bringing beauty into the world and taking in some cases what is most ugly - your experience of shame and the illnesses we all suffer from - and making them beautiful on a piece of paper.

Solly was connected to St. Joseph's hospital by Daniel Gabriel, who works for COMPAS. Gabriel said the work over the last couple of years has been so successful, that COMPAS is looking at expanding the program statewide, maybe even into neighboring states.

"If people are excited about life, excited about the possibilities of who they are and what they bring to life, it encourages them to work harder on their rehabilitation and encourages their mind body spirit to recover faster," said Gabriel.

A faster recovery translates to lower healthcare costs, or maybe the prevention of a new injury.

HealthEast and COMPAS are not alone in their quest to bring arts into the healing environment. Several other organizations across the nation have created their own programs to similar ends. And there are other programs cropping up across Minnesota. They've formed the Midwest Arts in Healthcare Network. A year from now the University of Minnesota will host an international conference on integrating arts in healthcare. Organizers hope the conference will draw attention to what appears to be burgeoning movement.

Actor and director Dean Seal leads the City Passport Theater group in a series of warm-up exercises. City Passport is a place for people "50 and better," as they like to say. It's located in the St. Paul skyway system, within easy reach of several independent senior living highrises. City Passport provides residents with a place to hang out, socialize, take classes and more.

71-year-old Katy O'Brien is one of City Passport's core actors. She's only just recently discovered her acting talent. Despite the fact O'Brien's recovering from a stroke and has a hard time enunciating, she was given a major role in the the theater groups comedy, titled "My ex-husband married your ex-husband's ex-wife."

"It's just a way to get us working together," said O'Brien. "In fact we have so much fun doing it, it's just a delight and it gets us all up and stretching. And especially the verbal exercises we do to get us ready for our talking.

Katy O'Brien uses a scooter to get her through the skyway system to rehearsal, but at rehearsal she's up on her feet, loosening up her limbs. She said the theater group gets her doing moves and exercises she wouldn't be nearly as interested in doing on her own, and she's seen a noticeable improvement in her stamina, her speech and her mood.

The health benefits of the artistic experience doesn't stop here. After several months of rehearsal, the City Passport Players have taken their 20 minute show on tour to a variety of nursing homes. There they play to crowds of people sometimes their own age, who company members say are craving a distraction from their own situations.

COMPAS's Daniel Gabriel said no matter who the patient is or what they're suffering from, they have the potential to benefit from a creative activity.

"Every one of those people is excited to have reasons to be alive each day," said Gabriel. "And the arts and the artists we send along to work with them help provide new reasons to get up in the morning and different ways to engage in life."

Gabriel said in the longterm, if such collaborations are to succeed between artists and caregivers on a grander scale, hospitals need to dedicate funding for the work, and people within the healthcare system must champion the use of art as a viable means of enhancing the recovery process.

Dear reader,

Political debates with family or friends can get heated. But what if there was a way to handle them better?

You can learn how to have civil political conversations with our new e-book!

Download our free e-book, Talking Sense: Have Hard Political Conversations, Better, and learn how to talk without the tension.