Lonely outpost marks US-Dakota War's start

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

A single building remains of the Lower Sioux Agency, once a government outpost and the hub of a small community on the Minnesota River near here.

Built to administer treaty obligations to the Dakota Indians, the place featured a doctor's office, an Indian agent's office, housing, a boarding house and a school. But 150 years ago today it became the focus of resentment that boiled into a war unprecedented in U.S. history.

Today marks the start of the US-Dakota War, which began with an attack, after a quarrel, by four Dakota Indians who killed several settlers near the tiny town of Acton, about 40 miles away.

ATTACKS GREW OUT OF LONGSTANDING RESENTMENT

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The killings were the impulsive act of four young men, but they followed years of growing resentment among the Dakota towards white settlers. By evening, all along the Minnesota River, Dakota leaders were weighing their choices.

The next day, on Aug. 18, 1862, the Lower Sioux Agency, the U.S. government's major presence in the area, felt the brunt of that resentment.

When word of the Acton killings reached Dakota leaders late on Aug. 17, they knew they had to act, said Anthony Morse, director of the Lower Sioux historic site.

"They felt that the only two ways that they could get out of that situation were to either give up the four boys to the United States government, or to protect the four boys and go to war," said Morse.

Even though their principal leader, Little Crow, said the Dakota would lose, the tribe chose war. On Aug. 18, the Dakota burned most of the buildings on the Lower Sioux Agency.

One of the first whites killed that day was a trading post owner, Andrew Myrick. In 1976, Mary LaCroix, Myrick's granddaughter, recounted the events in a recording housed at the South Dakota Oral History Center. LaCroix said she heard the story from her grandmother, Myrick's wife, who was hiding nearby and witnessed his killing.

"He went up through a trap door in the top of the building and then he jumped off the building. And as he jumped he sprained his ankle," said LaCroix. "My grandmother said one of these Indians stepped in the door, the other went around the part of the building and saw my grandfather there, so he shot him."

CORRUPT TRADERS CHEATED INDIANS

It was no accident that Myrick was one of the first targets of the exploding violence. When desperate Dakota tried to buy food on credit, the story goes that Myrick told them they could eat grass.

Traders were a focus of hard feelings because they dealt badly with Indians, said Sheldon Wolfchild, who is making a film about the causes of the 1862 war, based partly on David Nichols' authoritative book "Lincoln and the Indians."

The book documents a corrupt system of government aid that mainly benefited ambitious whites. Wolfchild, whose great-great-great grandfather, Medicine Bottle, was hanged after the war for his involvement, said that when the Dakota sold huge tracts of land to the government, they were promised payments of gold. But the traders ended up taking most of it.

"They would take the money off the top of the treaty money once a year when it came to the Dakota people," said Wolfchild.

Wolfchild said the government allowed the traders first claim on the funds to satisfy past Dakota business debts. The Dakota alleged those claims were fraudulently inflated. Government Indian agents often took kickbacks to overlook the corruption. In some years the traders took nearly all the Dakota treaty money.

President Abraham Lincoln's administration investigated the fraud allegations less than a year before the war started, Wolfchild said. The investigator, George Day, wrote Lincoln on Jan. 1, 1862, to say war tensions were building in Minnesota.

"Mr. President, I have discovered numerous violations of law and many frauds committed by past agents and a superintendent," Day wrote. "The Indians whom I have visited in this state and Wisconsin have been defrauded of more than $100,000 in or during the four years past. The whole system is defective."

In 1862, the year's treaty payments, including food, were two months overdue, and some Dakota were starving. So when the Acton killings occured, the Dakota went to war to erase white people from their lands.

"There's nothing comparable to it in American history, nothing," said Gary Clayton Anderson, a University of Oklahoma historian who has written several books about the war.

DAKOTA PEOPLE FELT 'UNDER SEIGE'

More people on both sides likely died in the 1862 Minnesota war than in any other government-Indian war.

"There's nothing comparable to it in American history, nothing."

The government was pushing the Dakota to adopt farming and live like white people. Missionaries also pushed for changes, including a ban on traditional Dakota dances. At the war council just after the Acton killings, Anderson said, it is likely the Dakota leaders felt under siege.

"These white people are trying to destroy our culture, they're trying to destroy us as a people, they're trying to destroy our religion, they're trying to destroy the way we live, our economy," said Anderson.

After leveling the government agency on the Lower Sioux, the Dakota warriors unsuccessfully attacked New Ulm. They also failed to take the principal government institution in that area, Fort Ridgely, about 15 miles southeast of the Lower Sioux Agency. On Sept. 2, a battle took place at Birch Coulee, near Morton, on the open prairie. About 150 U.S. soldiers found themselves surrounded, Morse of the Lower Sioux historic site, said.

"You can tell that it would have been a very difficult battle for them," said Morse. "Fire from all sides. Many of the horses were killed. I think some were even killed by the soldiers to be used as cover."

After a day and a half, the siege ended with the arrival of relief troops, who drove the Dakota away. Three weeks later, the war was over and the tribe was exiled from the state, its members deported mainly to South Dakota and Nebraska.

MASS EXECUTION

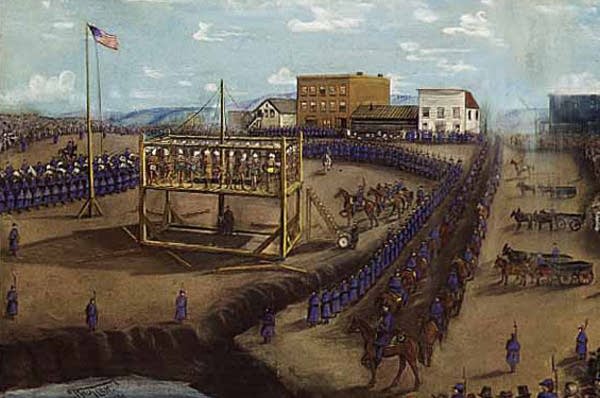

In December 1862, U.S. soldiers hanged 38 Dakota at Mankato for war crimes, most notably the killing of hundreds of settlers. To this day it remains the single largest mass execution in U.S. history.

New Ulm resident Alice Henle said some of her settler ancestors were driven from their farms by the war. Looking back, she said the 1862 war is understandable. When people are pushed, they'll eventually push back, she said.

"It's really a terrible thing what they did to the Indians," said Henle. "That they didn't have any food or anything. It's no wonder they got angry."

Upper Sioux tribal member Walter LaBatte said when he studied the war, the more he read the angrier he got, until one night he had a dream. His grandmother was a young girl in 1862 and saw the horrors of the war. In the dream, she scolded LaBatte for his anger.

"I remember her saying, 'That was my pain, that was my experience, not yours,'" said LaBatte. "I realized that she was right, that I shouldn't take on the pain of her and her contemporaries."

But for many Dakota the anger remains, as well as a desire to commemorate the war and its aftermath. That's evident in several events the Dakota have scheduled in connection with the 150th anniversary.

One is scheduled for today, when a group of Dakota will stage a symbolic return to Minnesota from exile, at the Pipestone National Monument in the southwest part of the state.