Northern Minn.'s St. Louis River comes back to life, but it's still not in the clear

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

When Gary Bubalo was a kid growing up on the far western side of Duluth, he and his friends would walk down to the St. Louis River at a place they called "Coolerator Hill," where an old air conditioning plant sat along the shore.

It was the 1960s, and the river was so polluted at the time — from nearly a century's worth of paper milling and other industry — that his parents warned him not to venture too close.

But some kids did anyway. "They were almost like social outcasts," he said, "because they swam in the river."

At Coolerator Hill, the river widens into a huge estuary — it looks more like a lake than a river — before it empties into Lake Superior.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"I remember one kid caught a fish once," Bubalo said. "He came up the hill and he was showing everybody, and it was like an alien from a[nother] planet or something — you could actually catch a fish in this thing!"

Bubalo is a financial advisor now. His dad worked at the U.S. Steel mill on the St. Louis until it closed in 1972, the year Gary graduated from high school. He remembers seeing the pipe where the plant discharged its waste, like a "constant dirty drain running right into the river."

Around the same time, farther upstream where the river tumbles down jagged rocks through Jay Cooke State Park, "you couldn't go down there and hang around the swinging bridge, because it stunk," recalled Jack Ezell, who grew up in Cloquet. He's now manager of planning and technical services for the area's sanitary district.

It's hard to imagine those scenes today. While the list of toxins found in the river decades later is still shocking — including PCB, dioxin and pesticides like DDT, dieldrin and toxaphene — the river has come back to life.

That spot where few kids dared to swim is now a campground and fishing dock teeming with honking geese. There's a ramp where anglers launch boats to fish for trophy-sized walleye and muskie. Others paddle canoes and kayaks among the wooded islands in the estuary.

The water is so much cleaner now that the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and other groups are starting to restore wild rice beds where they once flourished in the river's bays. Jay Cooke's iconic swinging bridge is now a destination.

"It's a pretty special resource," said John Lindgren, a fisheries biologist for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

"Within 25 miles of a 12,000-acre estuary there are a quarter-million people. But you can feel like you're actually quite secluded. And to have that high quality of a fishery in that close proximity to so many people is a pretty amazing thing."

But even as the St. Louis River's remarkable environmental turnaround is celebrated, there's still cleanup required. Toxic pollutants left over from the river's industrial heyday remain trapped in sediment. And an invisible pollution lingering beneath the water's surface still makes many fish pulled from the river unsafe to eat.

Reviving a giant

"I laugh and say it's a face only a mother could love," Anna Varian said as she helped hoist a 4-foot-long lake sturgeon onto a makeshift operating table. She was standing in a campground next to the St. Louis in Duluth's Fond du Lac neighborhood.

It's a bizarre-looking, sharklike beast, with four huge whiskers hanging down from its snout. Its puckered mouth droops several inches.

"You can see their skin is really tough," said Varian, the DNR's assistant fisheries supervisor for the Duluth area. She made a small incision into the fish's belly to insert a transmitter the size of a tube of lip balm. It will help researchers learn how often sturgeon swim upriver to spawn, and what kind of habitat they use.

The researchers also fitted each fish with a tiny transponder tag to chart its growth and to start estimating the size of the sturgeon population that spawns in the river.

DNR officials from Minnesota and Wisconsin started stocking baby sturgeon in the St. Louis River in 1983, decades after pollution and overfishing wiped out the giant fish from the river. Biologists with the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the Nature Conservancy and others rebuilt spawning habitat.

Sturgeon are highly dependent on good water quality to survive.

Slowly, steadily, numbers increased as the stocked fish took hold in the river. Five years ago, tribal biologists found their first fry from naturally reproducing sturgeon, a sign that a healthy fish population could grow on its own. Minnesota even began allowing catch-and-release fishing last year.

"It's been a huge success," Varian said of the long effort to bring sturgeon back to the river. "They're a beautiful fish, and an old fish, and it was very important to bring this fish back to the river for people to enjoy."

After stitching up her "patient" and letting the sturgeon recover in a metal tank, Varian slides it back into the river — something that, a few decades ago, likely would have killed it, thanks to a lack of oxygen in the water.

The return of the St. Louis River sturgeon represents a victory for environmental policy. The Minnesota DNR and others attribute the fish's rebound to water quality improvements prompted by the Clean Water Act and other regulatory efforts.

A work in progress

The campaign to restore the river dates back to the early 1950s, when state Rep. Willard Munger, DFL-Duluth, pushed for a regional sewage treatment plant to purify wastewater before industry and municipalities dumped it into the river, often virtually untreated.

Eventually state lawmakers approved the idea, but there was no funding for it until the Clean Water Act passed in 1972. That legislation, championed by late northeast Minnesota Congressman John Blatnik, was written largely by his then-staffer — and future congressman — Jim Oberstar, who died in 2014. The landmark law freed up more than $100 million in federal funding to build the facility.

Now, a 75-mile network of sewers delivers 40 million gallons of wastewater to the Western Lake Superior Sanitary District treatment plant in Duluth every day. The treatment process involves mixing the sewage with oxygen and bacteria, which feast on the waste. Several steps later, the water is cleaned and released. The whole process takes less than 10 hours.

"So, if you brushed your teeth last night in the city," explained Sara Lerohl, the treatment plant's environmental program coordinator, "certainly there are fish already out there swimming in your toothbrush water."

When the plant went online in 1978, one of its primary goals was to restore severely depleted oxygen levels in the river. The effect was almost immediate.

"To our surprise, by the summer of that year, we were already seeing fisheries start to redevelop," said Jack Ezell, who grew up in Cloquet and now manages planning and technical services for the area's sanitary district. "People were fishing and taking walleyes out of the river as early as 1979 again."

Still reasons for concern

But there's still a lot of cleanup work ahead, before the river can be considered fully recovered. A legacy of toxic contaminants remains trapped in the sediment. Underwater habitat that was destroyed by dredging for ship traffic has yet to be completely restored. The location of the old U.S. Steel plant remains a federal Superfund site.

About a decade after the sewage plant opened, a U.S. water quality pact with Canada listed the St. Louis River estuary as one of 43 Great Lakes areas of concern.

Minnesota, Wisconsin and the federal government began cleaning up polluted sites along the lakes. But progress was slow until 2011, when Congress began appropriating $300 million annually for Great Lakes cleanup.

Now the estuary is on target to complete its major cleanup efforts by 2020 — and to be removed from that list by 2025, said Nelson French, who's coordinating the effort for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. To get to this point, French said, between $300 and $400 million has been spent cleaning up the river.

Plans call for spending another $200 million in the next four years, about two-thirds of which would be federal money. Advocates are hoping for a $12 million state appropriation this legislative session.

"That gives us an idea of what the cost of leaving these legacies can be if you truly want to get them cleaned up," French said. "This tells a story of what it means if you don't regulate these materials."

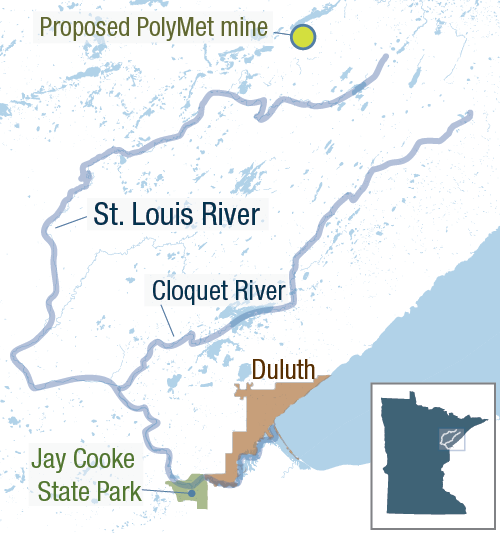

But even with the progress so far, the St. Louis River is hardly in the clear. Environmentalists argue that pollutants including heavy metals and sulfate could flow into the river if pollution safeguards at the proposed PolyMet copper-nickel mine, which if built would drain into the river's headwaters, fail to work.

"Proposed sulfide mining operations threaten to pollute the watershed and undo the excellent efforts of state, federal and tribal entities to reverse years of mining and industrial pollution," a coalition of environmental groups wrote to the Great Lakes Advisory Board.

PolyMet argues the environmental controls it intends to install will actually help clean the river by capturing and purifying existing polluted runoff from an old taconite mining tailings pond the company plans to reuse.

"Based on 10 years of working on an environmental impact statement, and having that statement finalized," explained Brad Moore, PolyMet's vice president of environmental and government relations, "it clearly shows that our company can meet all state and federal standards."

There's also a more immediate concern — pollution that some environmentalists say isn't getting enough attention. You can't see it or smell it like the waste that was dumped into the river through the late 1970s. This new pollution is invisible.

"We traded one set of devils for another," said Len Anderson, a retired biology teacher living on the Fond du Lac reservation outside Cloquet. He's spent many of his 76 years canoeing, fishing and fighting for the St. Louis River: He was one of a group of local residents who fought for the regional wastewater plant and helped develop the plan to clean up the river's legacy contamination.

"Now people are catching game fish, and they taste good, they look good and they smell good, but they have an insidious load of mercury like we've never seen before," he said.

Mercury pollution in fish is common in Minnesota waters. The state has identified unsafe levels of mercury in fish tissue in about 1,600 lakes and stretches of river. If too much contaminated fish is eaten, mercury can cause serious health issues, including brain damage in children.

A 2012 Minnesota Department of Health study found one in ten babies along the North Shore of Lake Superior are born with unhealthy levels of mercury in their bodies.

Most mercury is deposited into water through air emissions, from coal-fired power plants and other sources. The state has adopted a 20-year plan to slash the amount of mercury released from Minnesota smokestacks 76 percent from 2005 levels.

According to the state pollution control agency, that effort, combined with international pollution reduction efforts — most of Minnesota's mercury comes from around the country and around the world — should eventually lower the level of mercury in most of Minnesota's water bodies enough so that fish in them can be eaten safely once a week.

But in 10 percent of the state's waterways, including the St. Louis River, mercury levels in fish are so exceptionally high that they will fail to achieve lower mercury levels despite reduced air emissions.

Scientists still aren't exactly sure why mercury levels in waters like the St. Louis are so much higher than elsewhere.

It's likely the answer has something to do with how mercury gets into the food chain and builds up into higher concentrations in fish. It can only do that once it's converted to the chemical compound methylmercury, said Shannon Lotthammer, environmental analysis and outcomes director at the MPCA.

"Maybe there's some things that are causing the methylation process to happen more quickly or more intensely in some water bodies," Lotthammer suggested.

Critics like Anderson, the retired biology teacher, say the evidence in the St. Louis River is clear: High levels of sulfate released by iron ore mines that drain into the watershed are causing mercury to methylate and move up the food chain into fish tissue.

Lotthammer acknowledged sulfate plays a role. But she said other factors, including fluctuating water levels, also contribute to mercury retention in fish. "All of these factors have a role," she said, "and what we are trying to understand better is what are the key factors, and what are the management actions that we need to take ... to reduce mercury in the fish."

Anderson, though, feels the press of time. He's now battling a rare bone marrow disease. And given how long it can take to clean up polluted waters, he worries he won't see the day when his grandkids can eat all the fish they catch in the St. Louis — without risk to their health.

"I'm not going to live much longer," he said. "And I'm afraid I'm not going to get that goal accomplished."