In Duluth, restoring St. Louis River means dredging up the past

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

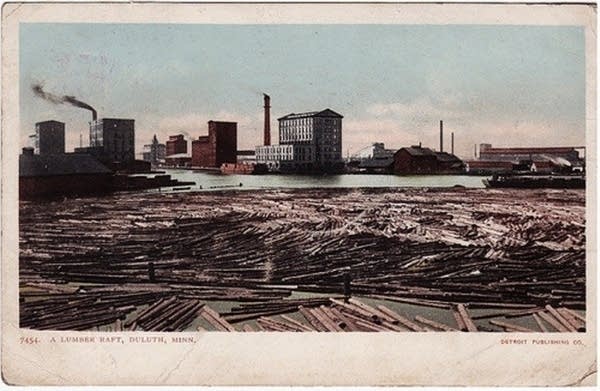

Duluth's fortunes were built largely on the iron ore and shipping industries. But for a short period of time, around the turn of the 20th century, Duluth was a timber town.

The industry, though short-lived, left its mark on the city’s St. Louis River, which lumber companies used as a timber highway to transport cut trees to the mills along its mouth at Lake Superior. Waste from those mills has clogged the bottom of the river for more than a century, wreaking havoc on its underwater ecosystem.

Now, a combination of state agencies is attempting to restore that ecosystem. But before it can revive the St. Louis River estuary, Duluth first needs to dredge up its industrial past.

From 1900 to 1910, Duluth sawmills produced more than 3 billion board feet of lumber. Laid end to end, that’s enough wood to cross the continental U.S. more than 200 times.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Thousands of people worked in mills built on docks over the St. Louis. Scraps of wood left over from processing were dumped directly into the water.

Even today, old logs and pieces of timber jut out of the water at odd angles along a shallow bay at the mouth of the river where it widens out into Lake Superior. It’s an area called Grassy Point, about five miles south of downtown Duluth.

There’s a wetland here, now a small city park, tucked next to a dock where ships are loaded with coal and limestone. At the turn of the 20th century, two large sawmills stood in their place.

As loggers clear cut what was described as an "ocean" of virgin white pine that stretched across northeast Minnesota, every spring they floated logs down the St. Louis River to Duluth. Some they transported by train.

"Putting the mills out on the water was convenient, because you could get the logs right into them,” said Melissa Sjolund, a habitat coordinator with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. “You could bring ships right up. And then also it was very convenient disposal, because as they’re sawing logs, they have end scraps, they have sawdust, they have reject pieces, and all of that just got dumped right into the river here."

Some of that wood was dredged up soon after it was dumped. Many of the millworkers lived in a nearby neighborhood called Slabtown.

"The folks were so poor that they would take these slabs of bark out of the river, dry them off, and that's the fuel they used for their stoves to heat their homes, to cook their food,” said Tony Dierckins, who detailed the city’s early years in “Lost Duluth,” a book he co-wrote with Maryanne Norton.

But most of that wood was left behind — in the river.

That wood now clogs the bottom of Grassy Point’s shallow bay. It's up to 20 feet thick in some places, most of it hidden underwater. All that waste has sucked the life out of this part of the river.

"You would expect a lot of vegetation growing in here that’s providing places for little bugs to live on, and for fish to come in and eat the bugs, waterfowl to eat the plants,” said DNR river restoration ecologist Pat Collins.

But “none of that is growing here,” Collins said. “It's all this wood. And it goes down so deep that it doesn’t allow for those sorts of plants to grow on it."

That’s important because those plants and microscopic bugs form the base of the aquatic food chain. The little fish eat plants and macroinvertebrates. Big fish eat the little fish. People catch the big fish. So by rebuilding the bottom of that chain, they hope to restore the aquatic ecosystem to full health.

“It maybe doesn’t get as much attention as a toxic, polluted site, but losing these valuable habitat types is something that’s happened as this area’s been industrialized and developed,” said Sjolund.

To restore this part of the river, the DNR will soon begin dredging up the wood — project coordinators estimate they’ll remove about 17,000 dump trucks full. But instead of taking it to a landfill, they'll use it to build new habitat for some of the plant and animal populations the restoration project is intended to revive.

The DNR will use the recovered old lumber to expand a tiny island nearby. When the project is complete, the wood will form the foundation of an 18-acre island that the DNR hopes will not only provide important shoreline habitat for birds and wildlife, but also help shelter the bay from wind and waves to foster aquatic plant and fish habitat.

But, even out of the water, that old wood won’t allow plants to grow on it. Their roots can’t attach to it.

So the next step of the project is to build up that brand-new skeleton of an island with sediment, dredged from the river bottom. At the same time the DNR is removing the submerged lumber, it will also be scooping out huge amounts of sediment that big storms have washed into nearby Kingsbury Bay.

A giant clamshell excavator now sits perched on a barge, scooping out the sediment that storms have washed into the bay over the last several decades. Some of this sediment was carried in by major flooding in 2012. All that buildup has prevented fish from spawning, and has choked the bay with invasive cattails, which grow heartily off its nutrients.

Sjolund said the DNR plans to take the good dirt they're scooping out of Kingsbury Bay and float it downstream to Grassy Point, where it will be used to cover the new island they're building with all the old wood left behind by the sawmills.

And by dredging out Kingsbury Bay, the DNR plans to restore valuable coastal marsh habitat, sheltered from waves and wind, that provides more places for crucial fish and plants to take root.

The excess sediment has destroyed habitat in Kingsbury Bay, but it can be used to help restore habitat at Grassy Point, said Sjolund. “It’s actually pretty valuable,” she said.

That’s because it contains the key to restoring Grassy Point’s ecosystem: the tiny bugs and plants that all that legacy wood waste has destroyed, microscopic biological life at the base of the aquatic food chain. Scientists call it “biomedium.”

Spanning 240 acres, at a cost of about $15 million, Sjolund said this is the largest habitat restoration project the DNR has ever undertaken. Paid for by a combination of federal and state funds, it's just one piece of a much larger effort to clean up the legacy pollution left behind by timber, steel, shipping and other industries in the St. Louis River.

Restoring habitat and cleaning up legacy contamination provides benefits beyond the environmental, said Barb Huberty, who heads up the larger St. Louis River estuary cleanup effort for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, a project that’s expected to be completed by 2025.

"This is not only a natural engine for the biology of this area, but it’s an economic engine,” Huberty said. “So as we clean it up, we’re revitalizing that economic engine.”

The city of Duluth hopes to use that revitalization to jump-start new development along its southwestern corridor. It's investing in river access points and trails to help draw tourists and new residents. City leaders hope that, in the end, the work will help emphasize that Duluth is not just a city on Lake Superior — it’s also a river town.

Dear reader,

Political debates with family or friends can get heated. But what if there was a way to handle them better?

You can learn how to have civil political conversations with our new e-book!

Download our free e-book, Talking Sense: Have Hard Political Conversations, Better, and learn how to talk without the tension.