Seraphia Gravelle: A voice for change on the Iron Range

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Protests large and small have emerged across Minnesota since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

All this week, MPR News is talking to some of the people behind rallies, marches and demonstrations happening beyond the Twin Cities metro area — about their experiences with race in Minnesota, why they march and what they hope for the future. See and hear all of the conversations here.

Before last month, Seraphia Gravelle had never organized a protest.

But then, George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police on Memorial Day. And she had an awful thought.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"My first thought was: Is my son's name going to be behind a hashtag one day?"

Gravelle’s 10-year-old son Graceson, her youngest, is Black. She’s raising him and his biracial siblings in the small Iron Range city of Keewatin, in a part of the state that’s almost 95 percent white.

When Floyd was killed and people started marching all over the state — and the country — she decided she needed to speak out, for herself and for her five children.

“Whatever it takes for things to change, whether I'm knocking down doors or marching in streets, that's what I'm going to do,” she said, “because I refuse to allow that to happen to my son, to his siblings, to his cousins, to his father, to his family, to any of them. I won't stand for it."

Gravelle was 17 when she moved to the Iron Range from Texas to live with her mom. That was more than 20 years ago. She’s Hispanic, and said she felt as though she stuck out when she arrived.

"I felt at the time I had to make a lot of changes to my appearance, to the way I spoke to people,” she said. “I call it putting on my ‘white voice.’ I had to take out the hoop earrings and replace them with studs and lower my ponytail and look the part. If I wanted a job, if I wanted to be accepted by the community, I had to look the part. And so I had to kind of whitewash myself."

But now, she said she is done with making people feel comfortable. And she’s not staying silent any longer.

So on June 1, one week after George Floyd was killed, she made signs and organized a series of marches in her region of northeastern Minnesota.

First stop: Keewatin, population 1,013. She gathered a group of about eight family members and friends, and marched down the city’s main drag, chanting “Black Lives Matter” and “No Justice, No Peace.”

Gravelle, 39, has lived in Keewatin for two years, but she said she was nervous about how her community would react. She only knows two Black kids in town, she said: Graceson, and his best friend, who lives down the street. She said she believes there’s a “genuine ignorance” when it comes to race on the Iron Range, because of a lack of experience with diversity.

But she was comforted when Keewatin’s police chief, Chris Whitney, met them at the beginning of the march. And Mayor Bill King introduced himself when the group arrived at the park in the middle of town to observe a moment of silence for Floyd.

"They took a knee with us,” Gravelle said. “And it was beautiful. We had nothing but support from the community."

King has also served as the city’s police chief.

"I don't care who comes into our community, we want them to feel welcome,” King said. “When a house is up for sale, we want it to be sold. And we want people living there. We want families. We want everybody.”

During the week after Floyd was killed, Gravelle wouldn't let her son go outside to play on his own. She just wasn't sure who in town she could trust. That's why she felt so strongly about organizing a march.

"People have to know. And people have to hear,” she said. “And I have to know what these people are like because my children play here.”

But by the end of that first march, she questioned whether the protest was even necessary. People had honked their horns in support. White people came out of their houses, raised their fists, chanted “Black Lives Matter” along with the marchers.

But she said their experience the next day in nearby Chisholm — just 20 minutes up the highway — was much different. Gravelle’s group of a few dozen people marched across Longyear Lake and through downtown.

"People were driving by and flipping us off and telling us to shut up,” she recalled. A guy drove past on his four-wheeler with a Confederate flag on the back, she said. A truck slowed down, revving its engine, the driver trying to drown out the protesters’ voices.

“But it didn’t matter. There was nothing that was going to drown us out,” said Gravelle.

Walking through downtown Chisholm, “our voices were just thundering through,” she said. “I loved it. I was like, ‘Y'all hear that? Can you all hear us?’”

Gravelle said that, growing up, she felt like she never really had a voice. Now, she felt empowered to wield it, loudly, echoing through the streets of her community, “behind something that you are so passionate about and so adamant about and stand so firmly on, so that the people in your community know, ‘This is who I am and this is who I'm always going to be and nothing is going to change that,’” she said. ‘“‘Y'all have to change.’"

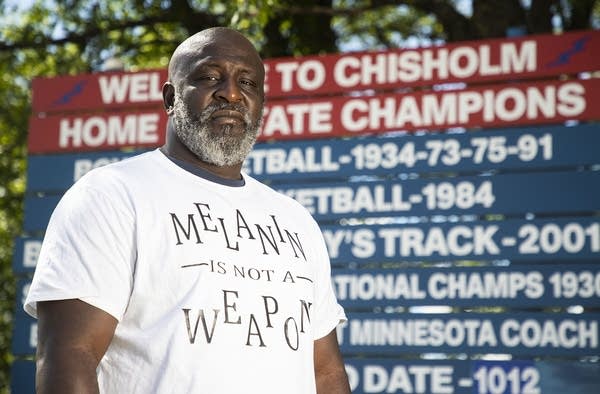

Gravelle enlisted Graceson’s father, Nathaniel Coward, to help with the marches. Coward moved to northeastern Minnesota from Florida in 1994 to play football at Vermilion Community College in Ely.

He said it’s important to march, even in small towns on the Iron Range, so people of color can make their presence known. He said he often feels invisible as a Black person in Chisholm. He said he often feels as though white people there “don’t even see us.” He said they don’t understand that there's “a community here, inside a community.”

Coward said the marches have been an important way to bring awareness — so people can’t ignore the concerns of people of color. He said diversity on the Iron Range is growing. And there are positive signs.

During the march in Chisholm, a white woman approached the marchers and handed out bottles of water after her husband, who had been fishing on the lake, called her to tell her what was happening. Later they invited more than 20 marchers over for a barbecue.

And the next day, Gravelle led the marchers back to Chisholm. The second day, she said, they received very little negative response.

Since the marches, Gravelle has joined a task force with the Hibbing Police Department to address racism. And she's organizing another march — this one in Hibbing — scheduled for July 25.

“I tell people all the time that I'm not going to sit down and shut up just so that you feel comfortable,” she said. “And I'm not going to stop until my brown kids are [as] safe as your white ones.”