Long-standing mistrust threatens to hamper testing in MN communities most vulnerable to COVID

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

From her perch inside a small vestibule at the Mexican Consulate in St. Paul — its ventanilla de salud, window of health — Rosalinda Alle does it all.

“I help people with resources, health education, preventative care, help them get tested for diabetes and blood pressure,” said Alle, a community health worker for St. Mary’s Health Clinics, which largely serves the uninsured and undocumented in the Twin Cities.

“I listen to a lot of stories about how there are a lot of barriers out in the community. It’s my job to see and be the voice of the Latinos,” she said.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Alle started hearing it all, too, from the families she’s gotten to know at the consulate — everything from misinformation claiming that COVID-19 testing actually causes people to get the virus, to concerns about being charged for a test.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

“They don’t trust all the information they hear, and they may trust the wrong information, too,” said Alle.

In August, this onslaught of misinformation prompted Alle and her colleagues at St. Mary’s to partner with local public health officials, churches and health care providers to open periodic testing clinics aimed at serving immigrants in the Twin Cities.

Pop-up clinics like these have become a key strategy in the state’s fight against the spread of COVID-19 among the very populations most likely to be severely affected by the virus. They serve as a gateway to an array of other services and resources that connect people to care if they test positive, and help them isolate themselves from family members and coworkers — a key factor in mitigating the spread of the disease.

And for public health experts, understanding just how many people have the virus helps them track and trace it.

But fear and distrust rooted in long-standing economic and health disparities can be barriers to testing among communities of color — and particularly for undocumented immigrants who fear their personal information may be used to deport them. It’s created challenges in public health workers’ efforts to mitigate the spread of the virus.

Long-standing disparities

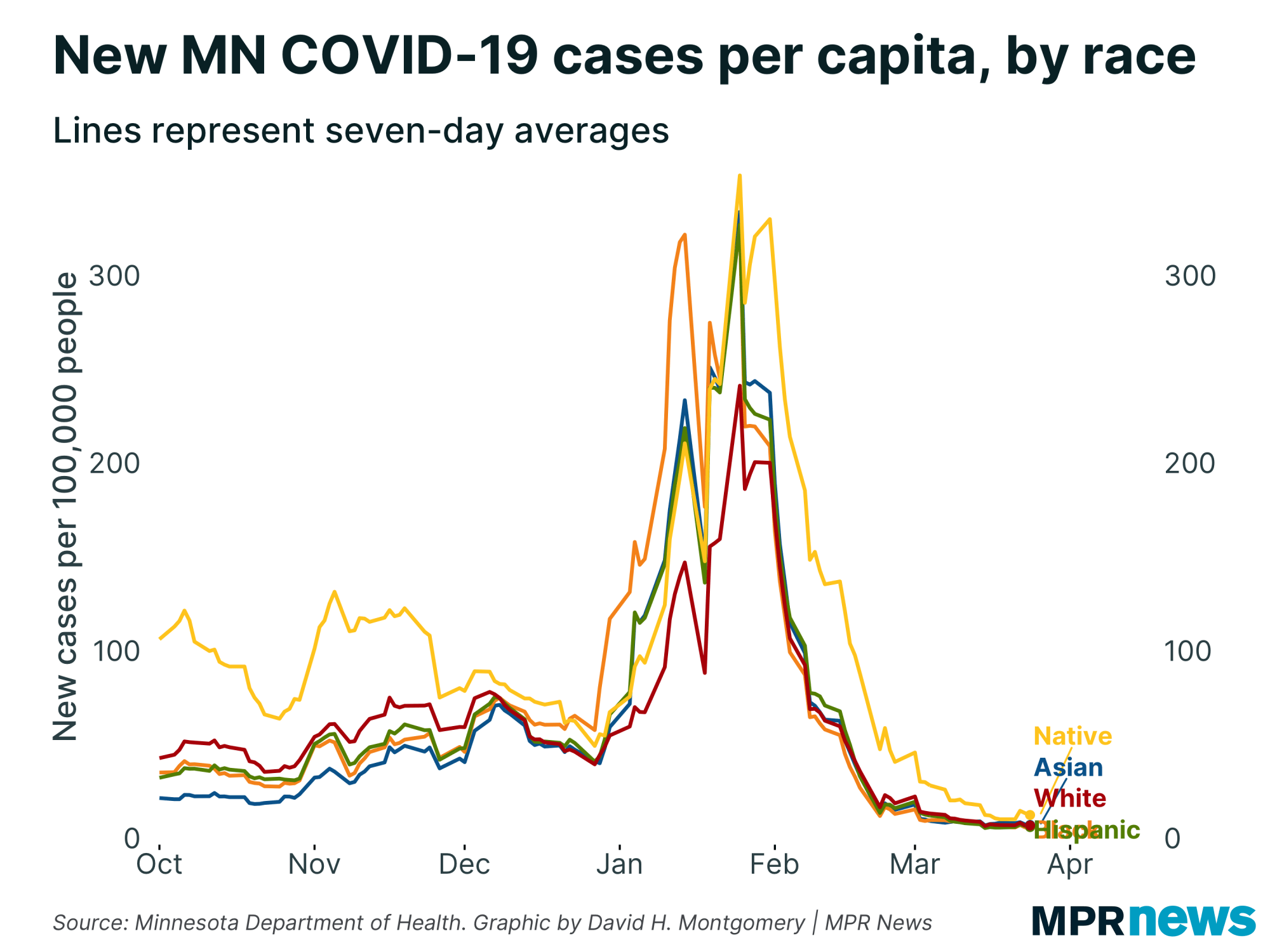

Latinx Minnesotans are testing positive for COVID-19 at about five times the rate of white Minnesotans. And along with Black Minnesotans, Latinx Minnesotans are also being hospitalized and moved to intensive care units at higher rates than the overall population.

Similar trends hold true for Minnesota’s Indigenous and Asian residents.

In part, these statistics reflect a long-standing and complex web of health and economic inequities among people of color, said Kou Thao, who directs the center for health equity within the Minnesota Department of Health.

People of color in Minnesota are more likely to be working jobs that have been deemed essential during the pandemic — like food production or retail — that make it more likely they’ll come in contact with the virus and spread it.

At the same time, people of color in Minnesota are statistically more likely to have preexisting conditions that put them at a higher risk of having a more severe case of the virus, said Thao.

Thao said the disparities laid bare by the pandemic are complicated by long-standing fear and distrust of the government and medical institutions.

“We hear stories all the time, even before COVID, for many communities of color and American Indians, that because of distrust or not having access to insurance, folks wait to get care until it’s really bad, and they wait until [their sickness] requires an ER visit,” he said. “We’re seeing the same applied to COVID.”

‘If they’re invisible, they won’t get deported’

In the early days of the pandemic, getting a test in Minnesota wasn’t easy. Limited supplies and a scramble to build processing capacity meant tests were reserved for only the sickest.

That has changed over the course of the last six months — but not for people who don’t have insurance, said Cristina Flood Urdangarin, St. Mary’s Health Clinics’ community health outreach manager.

“[The undocumented] are told to go see their primary care provider, but they don’t have a primary care provider,” said Flood Urdangarin. “We’re talking about a group of people, most of them don’t have insurance.”

Those logistical barriers are complicated by fear and distrust, said Sister Margaret McGuirk, who helped organize the testing clinics. She said undocumented immigrants are scared of being deported, so they don’t do things where they have to give out information — like go to the doctor.

“They’ve learned that if they want to make it in this country, they have to be invisible,” said McGuirk. “They’re invisible in the restaurants, they’re invisible in lawn care — they’re invisible everywhere. And if they’re invisible, they won’t get deported.”

‘How will I put food on the table?’

To promote the August clinics, Flood Urdangarin said organizers relied on social media, radio and word of mouth — channels of communication the Hispanic communities St. Mary’s serves typically consider to be trustworthy.

Organizers didn’t require advance registration for a test, and the clinics were held on Saturdays to avoid most work conflicts.

Test-takers were asked for minimal contact information, and the testing was free.

Location mattered, too, said Flood Urdangarin. The clinics were held at The Church of the Incarnation/Sagrado Corazon de Jesus, a church in south Minneapolis with deep ties to the city’s Hispanic community, where St. Mary’s has hosted annual flu clinics in the past.

“Going back to the same location, immunizing the community every year, we saw that we gained their trust,” she said. “We knew that if we did it in a church, or in a place they are used to, it would be easier for them.”

Turnout was higher than expected, said Flood Urdangarin. More than 800 people were tested between the two August clinics. The clinics were so successful that more were held in September, with plans for more in the future.

Meanwhile, the Minnesota Department of Health is in the midst of a free, statewide testing campaign in part aimed at underserved communities.

But even when logistical barriers like cost and location are eliminated, Alle said her clients’ fears don’t end. Many of them live paycheck-to-paycheck working jobs that can’t be done remotely.

If they test positive and they’re undocumented, they can’t collect unemployment, either, she said.

“I’m asked, ‘How many days will I be out of work? How am I going to pay rent? How am I going to put food on the table?” said Alle.

Flood Urdangarin said without financial support for people who test positive — especially for those who can’t collect unemployment — she fears her clients will go to work anyway if they have mild symptoms, perpetuating the virus’s rampage through the very communities that are most vulnerable to COVID-19 in the first place.

“All those concerns are totally real. They need to go out and make money,” she said. “If you put yourself in their shoes, you understand it.”

If you go: COVID-19 testing in Minnesota

Minnesota is in the midst of a monthlong testing push, with pop-up clinics around the state. Tests are free to anyone, and getting one doesn’t require insurance.

COVID-19 in Minnesota

Data in these graphs are based on the Minnesota Department of Health's cumulative totals released at 11 a.m. daily. You can find more detailed statistics on COVID-19 at the Health Department website.

The coronavirus is transmitted through respiratory droplets, coughs and sneezes, similar to the way the flu can spread.