What's to come for Minnesota and COVID-19? Here are three theories.

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Minnesota is on track to see this fourth COVID-19 wave peak in the next week, but what will happen next month remains uncertain.

Minnesota is averaging around 1,200 cases per day, which is up from about 900 cases per day a week ago. How can a peak be near when the state is still seeing cases rise to levels unseen in months? That’s exactly what a peak is: when cases stop rising. Until the peak arrives, we can expect cases to keep rising to new highs.

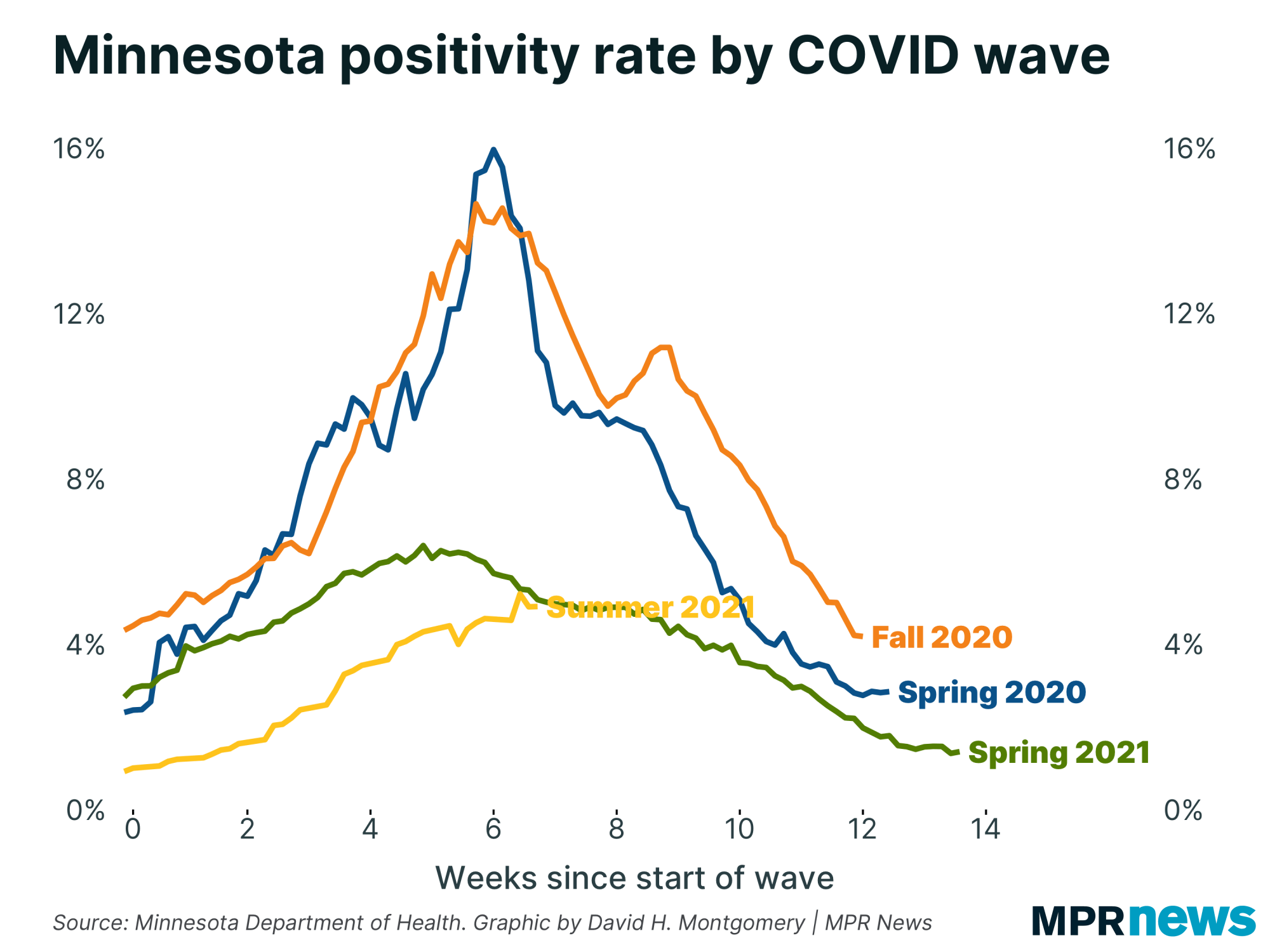

But raw case counts aren’t always the best gauge of how things are going. Though sometimes they’re the best data available, not everyone who’s sick gets tested, so case counts tend to rise when testing goes up. A solid metric for tracking the spread of COVID-19 is positivity rate, which controls for testing volume. Here’s how the state’s positivity rate has been changing, compared with past waves:

Eventually we’ll get to a point where our positivity rate is below what we saw two weeks ago. As the chart below shows, extending the pace out linearly from when positivity rate stopped accelerating in late July, we’re forecast to peak around Sunday:

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

This is more art than science, as the rate has jumped around a bit. It wouldn’t be shocking now to see another big drop bring that peak sooner or to see the slower pace of the past few days continue, stretching this out into next week. It’s also entirely possible that having crept right up to the edge of a peak, our wave ends up shifting back into growth.

Here are three different theories for what the future could hold for Minnesota and COVID-19: the pessimistic theory, the seasonal theory and the optimistic theory.

The pessimistic theory

Here are the elements of the theory underlying this pessimistic argument:

The extra contagiousness of the delta variant means this wave will act differently than before.

Prior waves were at least somewhat constrained by measures like mask mandates. With those no longer broadly in place, the virus will spread faster.

Upcoming big social gatherings like the Minnesota State Fair, Labor Day and the start of school will provide an accelerant for infections, especially with fewer mask mandates.

While places like Minnesota have had relatively mild waves so far, we’re not that different from places that have had explosive delta waves and can expect to follow in their footsteps.

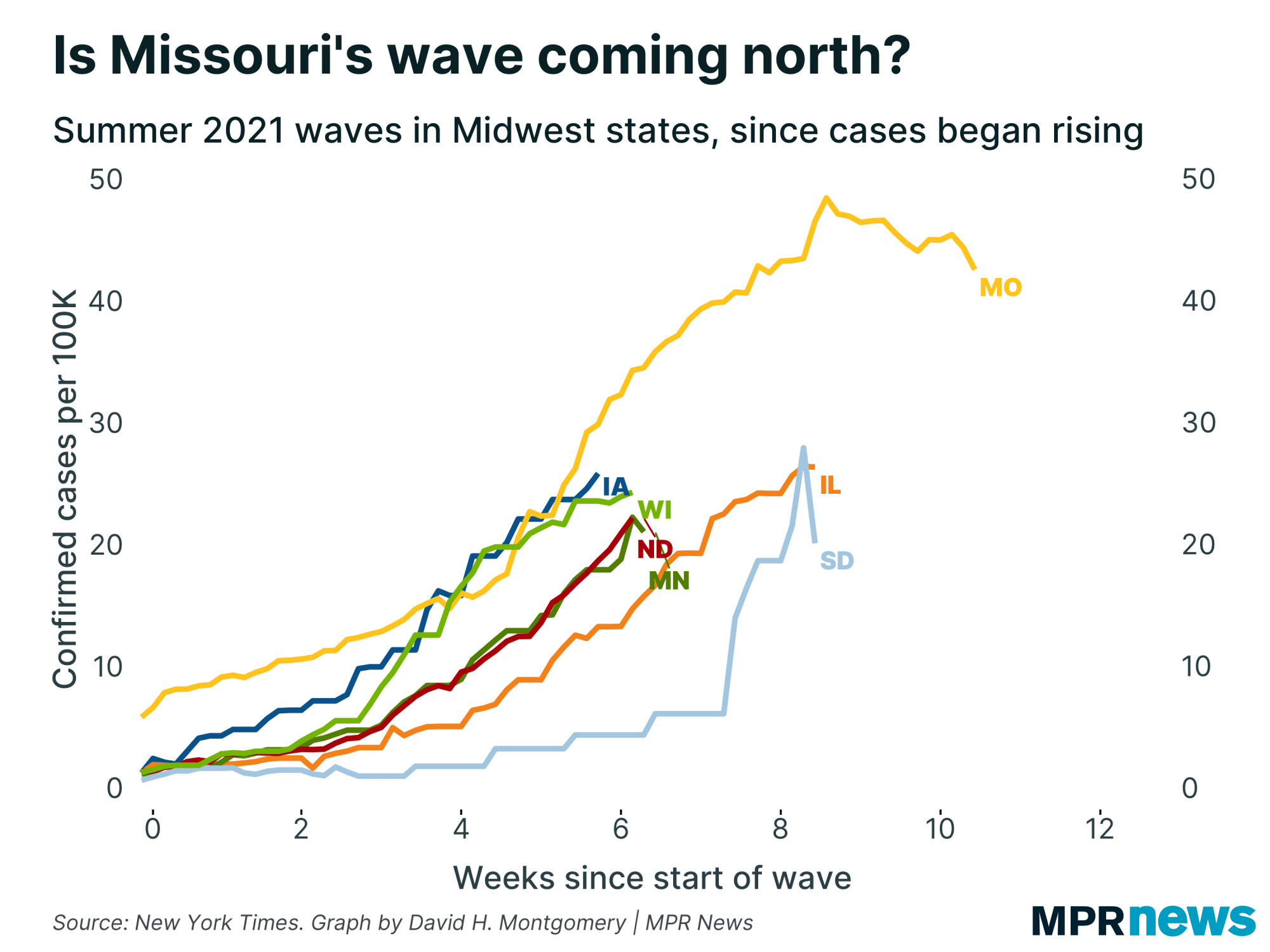

Looking at the per-capita case rates in a range of Midwestern states bolsters the pessimistic case:

There are two striking things that a pessimist might find persuasive.

The first is the light blue line, representing cases per capita in South Dakota, which has shot up dramatically in recent days (though it did tick back down sharply again today, suggesting that at least some of the volatility might be data related). It’s possible this is connected to the recent Sturgis Motorcycle Rally there, and it's possible that these cases are going to move east into Minnesota over the coming weeks.

The other is Missouri, which began its current wave a month earlier than the other states here. Missouri saw cases rise to much greater heights and last for longer than the more common six or seven weeks. Here’s that same graph, but with all the states crudely aligned from the day when cases first began rising this summer:

If Missouri's past is Minnesota's future, then far from being on the verge of peaking, we're in line for four more weeks of rising cases before finally peaking. (That's something similar to what the Mayo Clinic's model predicts.)

The seasonal theory

The seasonal theory is that we'll peak imminently but then will start a fall wave in a month or two. Here are the arguments behind this theory:

The data says Minnesota's case growth is slowing, and there's no good reason to believe it's wrong.

COVID-19 is at least to some degree seasonal, with warm-weather areas likely to have waves in the summer when everyone goes inside for air conditioning, easing transmission of the virus. Cold-weather areas, in contrast, are likely to get their worst outbreaks in cooler months.

Therefore, while Minnesota may skate by with a relatively mild summer wave, it'll get smacked later this fall like southern states are now.

While the pessimistic argument builds on what happens in the very recent future, the seasonal theory builds on observations over the past two years, like how the South has largely not been hit by spring waves in 2020 or 2021, but has been hit by summer waves, while northern areas have tended to have milder summer infections but worse spring and fall waves.

If this is true, an imminent peak is only temporary good news — a fifth wave awaits us.

There’s also a second set of arguments that gets you to a fall wave without going hard on the seasonality factor. That's to take the pessimistic arguments above about how the start of school, the Minnesota State Fair and other issues will spread the disease, but assume it will take time for this to take full effect. Instead of a continuing spike now, the argument goes, we may peak, but the wave will get a second wind by late September.

Minnesota's data actually shows signs of "second winds" with past waves, too, though they've always been fairly brief and mild. It wouldn't be a surprise or cause for panic if we see a brief uptick in cases in early September — but also this limited sample doesn't prove that any September uptick we get will be as mild as the last three aftershocks were.

The optimistic theory

The third case to consider is the optimistic argument. Here’s what’s behind this theory:

An increasingly dominant share of Minnesotans already have resistance to COVID-19, from vaccination or prior infection, thus increasingly limiting the virus's ability to spread freely.

So while COVID may not go away entirely any time soon, any flare-ups will be relatively moderate.

The people who do catch COVID will be unlikely to die or suffer serious health risks, since most of the older or at-risk people are already immunized.

The driving idea behind this one: Even with more dangerous variants out there, Minnesota's summer wave was milder than our spring wave, which was (much) milder than our fall wave. If this is just due to rising population immunity, we should expect this trend of diminishing waves to continue.

Of course, the experience of southern states this summer shows the ways this argument could be wrong, too — while most of them are less vaccinated than Minnesota, they all still have far more population immunity now than they had last fall or this spring and still got walloped.

People who endorse this argument are also drawn to graphs like this one, showing the diminishing mortality of COVID-19 over the past year, even as cases continue to spread:

All three of these theories have strong arguments behind them. It's important not to fall prey to confirmation bias in deciding which one you think is true.

Read the full version of this article in our COVID newsletter.