'Incredibly powerful' Hurricane Lee will see 180 mph winds, forecasters say

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

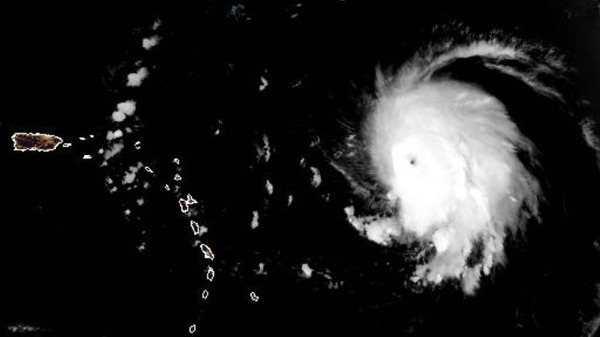

Hurricane Lee has grown shockingly fast, and it's not done: its winds are forecast to top 180 mph by Friday evening.

For now, Lee is an “incredibly powerful” Category 5 storm with 165 mph winds, the National Hurricane Center says. But thankfully, it's not currently threatening to make landfall anywhere in the U.S. or the Caribbean.

That doesn't mean no one will experience any effects from Lee. The hurricane's sheer power will bring dangerous beach conditions to Puerto Rico and other islands on Friday and Saturday. By Sunday, “most of the U.S. East Coast” will see dangerous rip currents, according to the NHC.

The latest forecast sees the heart of the storm staying well north of the Leeward Islands, the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico as it moves west-northwest across open water this weekend and early next week. Hurricane Hunter aircraft ventured into the storm's eye early Friday, to monitor its intensification.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Next for Lee: more power, then growth

It took just 24 hours for Lee's maximum sustained winds to roar from 80 mph to 160 mph, from late Wednesday to late Thursday. It is now roiling the ocean, with waves peaking between 45 and 55 feet near its center, according to the NHC.

If you're thinking it's early for a hurricane to reach this stature, you're not wrong. As hurricane expert Michael Lowry says, “Lee is the farthest southeast we've ever observed a Category 5 hurricane in the Atlantic since records began 172 years ago.”

The fearsome storm is expected to keep adding power on Friday, before starting to ramp down its gaudy windspeeds a bit late Saturday and early Sunday. Still, it's expected to solidly remain a major storm through the coming five days.

Up to this point, Lee has been relatively small, compared to its power. But the storm is expected to get larger over the weekend and into early next week — extending the threat of its dangerous ocean swells.

While its winds are exceptionally fast, the storm is predicted to slow its movement over the water to a near crawl. As of Friday morning, Lee was moving west-northwest at close to 14 mph, but the NHC predicts "a significant decrease in forward speed."

For people monitoring Lee from the Bahamas to the East Coast — and trying to guess when the slowing storm might pivot to the north — the coming days might feel like watching a soccer player stutter-step as they prepare to take a penalty kick. As of now, the NHC's five-day "forecast cone" shows only a slight nudge to the north, next Wednesday.

All eyes are on the storm's path

So far, the storm isn't posing an immediate threat to anyone on land. But experts advise keeping a close eye on the storm.

“It is way too soon to know what level of impacts, if any, Lee might have along the U.S. East Coast, Atlantic Canada, or Bermuda late next week, particularly since the hurricane is expected to slow down considerably over the southwestern Atlantic,” the NHC's John Cangialosi wrote in his discussion of the forecast.

There is a chance Lee might not make landfall anywhere. Several long-range models predict Lee will curve north — missing islands along the Caribbean and staying clear of the U.S. mainland. While models are generally accurate, they're not perfect. In 2017, Hurricane Irma was supposed to follow a similar path — but it wound up smacking Florida's Gulf coast.

Warm waters are intensifying Lee

The system has gained power passing over “record-warm waters of near [86 degrees Fahrenheit] east of the Lesser Antilles,” the NHC said, adding that such warm waters are more likely to be found in the Gulf of Mexico, not the Atlantic Ocean.

The frequency of intense and damaging tropical storms and hurricanes have been linked to climate change. As NOAA has stated, “Warming of the surface ocean from human-induced climate change is likely fueling more powerful tropical cyclones.”

The storms' destructive power is then magnified by other factors related to global warming, from rising sea levels to more intense rainfall totals.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.