A Girl Scouts troop offers hope and ‘sisters for life’ for migrant children

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

The world is very gray today: It’s raining in New York City.

From the outside, the building looks like any other old hotel in midtown Manhattan, but it is one of the largest migrant centers for families with children in the city. About 3,500 people are housed here.

Inside the building, the light is dim and there’s the constant murmur of people shuffling in and out. Somewhere in this labyrinth of hallways, there’s a room that’s in technicolor.

This is the meeting point for a Girl Scouts troop, in partnership with New York City Health and Hospitals.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

One by one, the scouts start trickling in. Their ages are kindergarten through 12.

They all are recently-arrived migrant children from Latin America, whose families are seeking asylum.

Once they sit down, the first order of business is to share how’s their mood this day.

“How do you feel today?,” asks Juliana Alvarez, a volunteer troop leader, as she turns to a girl named Alicia, whose hand is raised. She tries to respond in English.

“Happy and... happy and... Valiente!” she smiles. Valiente: brave. Turns out, Alicia got a shot today and she didn’t cry once.

Alvarez turns to another girl, Tahanne. “How do you feel today?”

“Kind of sad.” She answers. “Tomorrow we have to leave this shelter.”

The other girls groan sympathetically. They are all part of the approximately 180,000 migrants who have arrived in New York City in the last two years.

Overhelmed by the numbers, the city government has implemented a 60-day rule for shelter stays.

For Tahanne’s family time is up. She says she doesn’t know where they are going to live the next day.

“(If) it’s difficult for adults, imagine how hard it is for a child to understand why they are here,” says Alvarez, the volunteer mom leading the troop this day.

She knows exactly how these kids feel. She and her two daughters lived in this shelter for about a year.

Alvarez had to leave her native Colombia when a local gang threatened her family. “I was scared,” she says. “I heard that on the journey to the U.S. you get raped or killed.”

Her journey was terrifying, she says. But once in the U.S., she knew she had be strong for her children, who weren’t fully grasping what was happening. “My kids would ask me, when are we going back home to Colombia? Or, mom, why have we been eating pizza every day for four months?”

Dreaming of becoming a doctor

During one of the breaks, I got a chance to talk with 10-year-old Tahanne, the girl scout who is sad today. She’s from Ecuador.

I asked what she’d like to do when she grows up. She answers with a question: “Do you know what the sternocleidomastoid is?”

I have no idea. Tahanne points to her neck. It’s a muscle, she explains. She wants to be a doctor.

Shereen Zaid, senior director for logistics for New York City Health and Hospitals says that the 60-day rule has affected the program. “If you don’t have consistent people every single day, how do you still make an impact? Consistency is key.”

But Zaid says if girls attend at least some meetings, that would help.

“If we could have some of the girls meet twice or three times a week and just color together, or sing together or talk about community development together, that is such a win,” Zaid said. “They come here with a suitcase or one backpack and so we are trying to help them live an actual fulfilling life.”

Tahanne’s family can reapply to stay here or to go to another shelter. According to the city comptroller, 45 percent of families whose time has ended, have been able to stay in the shelter, or transfer.

If Tahanne’s family can’t stay here, she has the option to still connect with the Troop 6000 via zoom. She frowns at that prospect.

“We share everything here. We come her to be friends, these are my sisters now,” she says.

“This is probably the only sense of stability they have right now,” says Giselle Burgess, founder and senior director of Troop 6000 for families living in the NYC shelter system. She got the idea over a decade ago, when she and her daughters were living in a shelter in Queens.

She says in the last couple of years, as migrants started coming into New York, the troop was ready to create this chapter of Girl Scouts.

She first needed to adapt the curriculum.

Take an activity like the cookie sales, which Girl Scouts are famous for. Here, it turns into an exercise in math and learning American currency.

And all around the room there are drawings of the New York City Subway lines, and penciled maps of the city.

Also, they write handwritten letters. This was part of another recent project: write a letter to girls who want to come to America.

One of them, written by a 9-year-old scout:

My advice for girls who want to come to the US

Is that you have to be very strong

And you have to really want it

Because this country has a lot of opportunities

But the journey will not be all easy.

This letter is a stark reminder that many of these kids recently made a journey that is dangerous, even deadly.

In the next break of the group, I chat with a 12-year-old girl from Venezuela, named Astrid. “When I grow up, I want to save people. A lot of people die.”

She says she wants to join the U.S. military. “I’m ready,” she says. “I walked through the jungle to get here... I’m ready.”

The Troop has two Master of Social Work candidate interns, who attend every meeting and monitor the children for signs of trauma, anxiety and depression.

“Outside of these doors, it is trauma,” says Meredith Mascara, CEO of Girl Scouts of Greater New York.

When she looks at these girls, she thinks about when she heard her own grandparents talk about immigration, she says.

“They will be the ones running the city. I’m sure we have (future) elected officials that are passing through (the shelter system.) The story goes on. It’s what our relatives did. They’ll be telling those stories to their kids and to their grandkids,” she says. “I’m proud that Girl Scouts are part of that.”

But for now, it’s fun and games. Snacking and learning to pronounce Girl Scout cookies with names that, for non-English speakers, might as well be called sternocleidomastoid cookies.

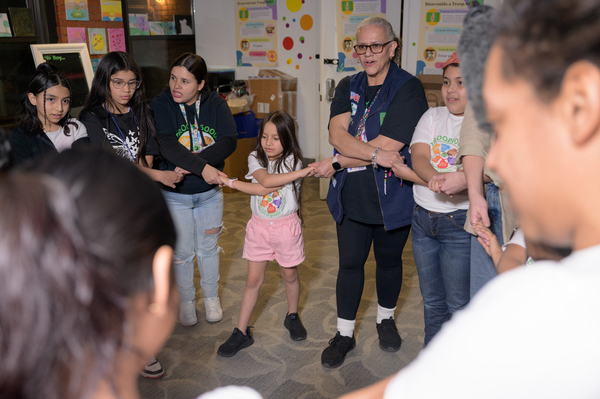

By the end of the meeting, the girls stand in a circle, holding hands. The troop leaders sing the traditional Girl Scout goodbye, the scouts try to follow along.

Make new friends, But keep the old.

One is silver, And the other, gold.

A circle’s round. It has no end.

That’s how long. I’m gonna be your friend.

Outside, the world can feel like it’s on fire. But in this tiny corner of the shelter, it’s always a good day to make new friends.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.