‘I don’t wish this to anybody’: How COVID is disproportionately hitting Minnesota’s Latino community

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

The last time Emilia Gonzalez Avalos saw her father healthy, he surprised her at her home with breakfast and a pot of coffee. It made her day.

“Then we chatted for a little bit, and he said, ‘You know, I'm feeling uneasy. … I am tired, I don’t know what’s going on,’” Gonzalez Avalos recalled.

Her father went home that November morning, and a few days passed. Then a phone call: It was her uncle, telling Gonzalez Avalos that she’d better check on her dad because he’d been coughing. She grabbed a mask and raced to his house.

“When I opened the door to his room, he was just laying on his bed,” she recounted. “His eyes have really deep dark circles. He looked very sick. And when he saw me, he tried to get up and pretend he was fine.”

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

But he couldn’t even get onto his feet. Gonzalez Avalos rushed him to the emergency room, despite his misgivings — he was worried about the bill. When they got to the hospital, doctors told Gonzalez Avalos her father’s oxygen level was low and that he had “COVID lungs.” On Thanksgiving Day, he took a turn for the worse and was put on a ventilator.

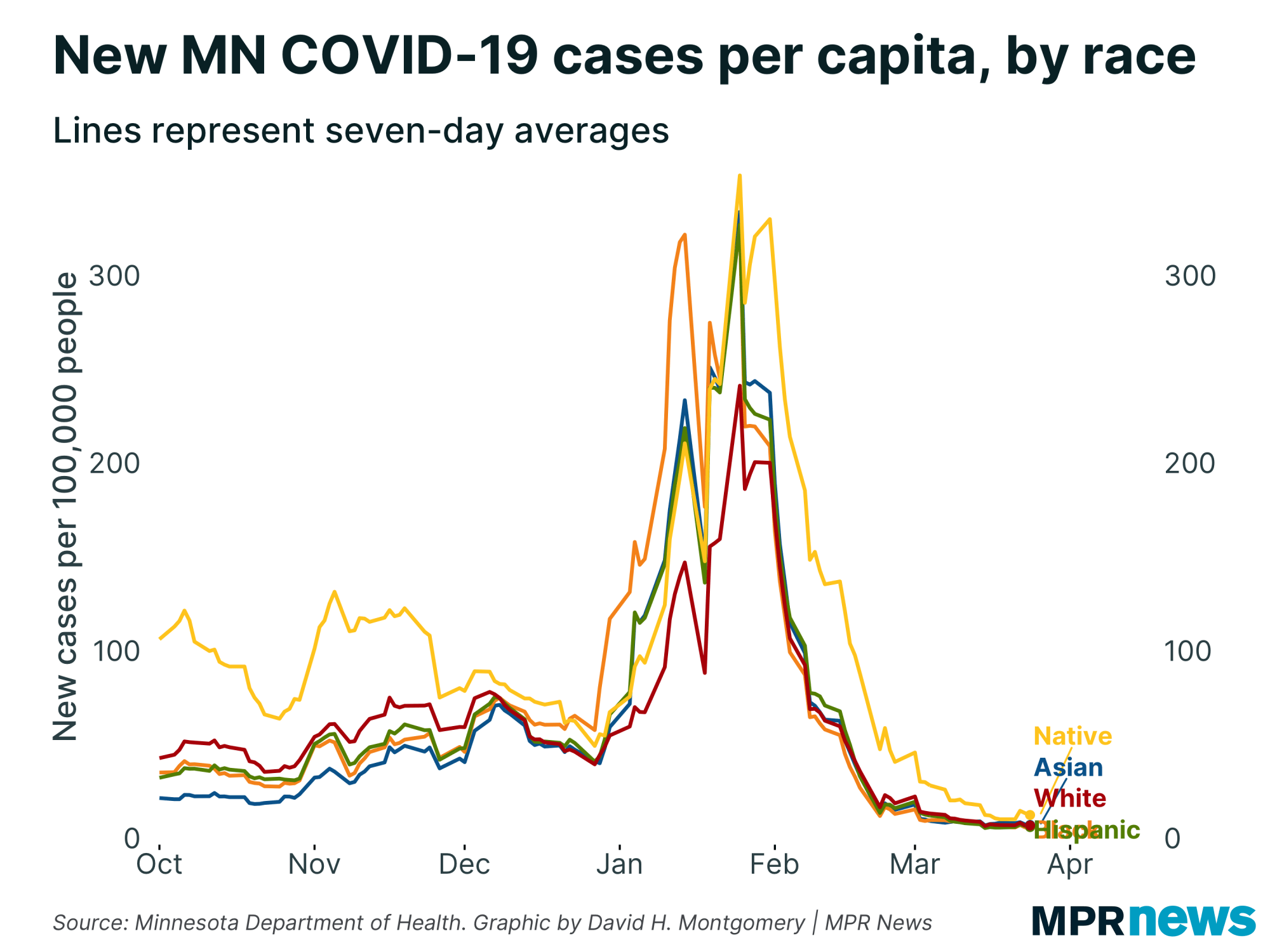

The rising COVID-19 cases are startling everywhere, but the rates in the Latino community in Minnesota and across the country are particularly alarming. Many Latinos work essential jobs that can't be done remotely and are more likely to be exposed to the virus. And those who are not authorized to be in the country are in a particular bind: They don’t qualify for government benefits that can be a financial lifeline for families struggling during the pandemic.

Recent data from the Minnesota Department of Health shows that 11 percent of those admitted to intensive care units with COVID-19 have identified as Hispanic. Minnesota’s Hispanic population is just 5 percent.

Essential workers

Public health officials say they are not aware of a specific event or outbreak that has contributed to the spike in cases in the Hispanic community. But with many Latino immigrants filling essential jobs in places like construction sites, food-processing plants and cleaning companies, community organizers say these workers don’t have the luxury of working from home to limit their exposure to coronavirus.

Gonzalez Avalos’ dad is 66. Originally from Mexico, he lacks authorization to be in the United States and has been waiting for documented status since 2001. Meanwhile, he's worked jobs in construction, and most recently has been finding work through a temp agency. The last job he had was packaging food.

Gonzalez Avalos said the only way she’s been able to connect with her father is through the hospital’s iPad. It’s hard waiting for any piece of news.

“Those doctors are truly fighting to save his life,” said Gonzalez Avalos, the executive director of the Latino community group Navigate MN.

The Minnesota Council on Latino Affairs conducted several listening sessions over the summer inviting community members to share how they’re coping during the pandemic. They spoke of working conditions, financial pressure and distrust in government, said executive director Rosa Tock.

Some fear that they might risk their immigration status by seeking benefits such as food assistance and unemployment benefits, Tock said. Others are also afraid to test for COVID-19.

"There is some perception already in some communities that the info would not be confidential and be shared with other federal entities,” she said.

‘I’m going to lose my mom’

The impact of the coronavirus on working-class Latinos has worsened since then.

Catalina Morales, 29, recently found herself in line with more than a dozen cars waiting to get tested for COVID-19 at a drive-up site in the Twin Cities. It was only 7 a.m., but she and her sister got there nearly two hours before the site opened in hopes of beating the crowd.

Morales, an organizer with the group Faith in Action and University of St. Thomas college student, spent last month taking care of her critically ill mother and sister in Illinois. Family members suspect they were exposed through her brother-in-law, who works in construction.

Morales stayed in a hotel room with a kitchenette and made food for her little nieces while her mother and sister spent several days at the hospital. Morales’ sister was in the intensive care unit.

Morales was so consumed by the thought of losing her mom and sister that she didn't have the capacity to think about hotel and travel costs and any forthcoming medical bills.

"There was a set of days that we were, like, my mom and sister are both going to die,” she said. “One: I'm going to lose my mom, but then the second thing is thinking what are my nieces going to do without their mom?"

Both relatives eventually recovered and left the hospital. Morales's brother-in-law is back at work after losing about a month of income.

But for Emilia Gonzalez Avalos, the tough journey with the disease has not yet ended.

On Twitter she posted a side-by-side screenshot of a recent Zoom call showing in one picture herself and her young son. The other side revealed a heartbreaking picture of her dad. He was lying in a hospital bed while hooked up to a device to support his breathing.

“This is how my kids have to visit their abuelo who is in critical condition,” she wrote. “His face is blue. My son remains in the corner because he is scared and yells ‘te amo’ from afar. There are very different kinds of pain in the world. Again, I don’t wish this to anybody.”